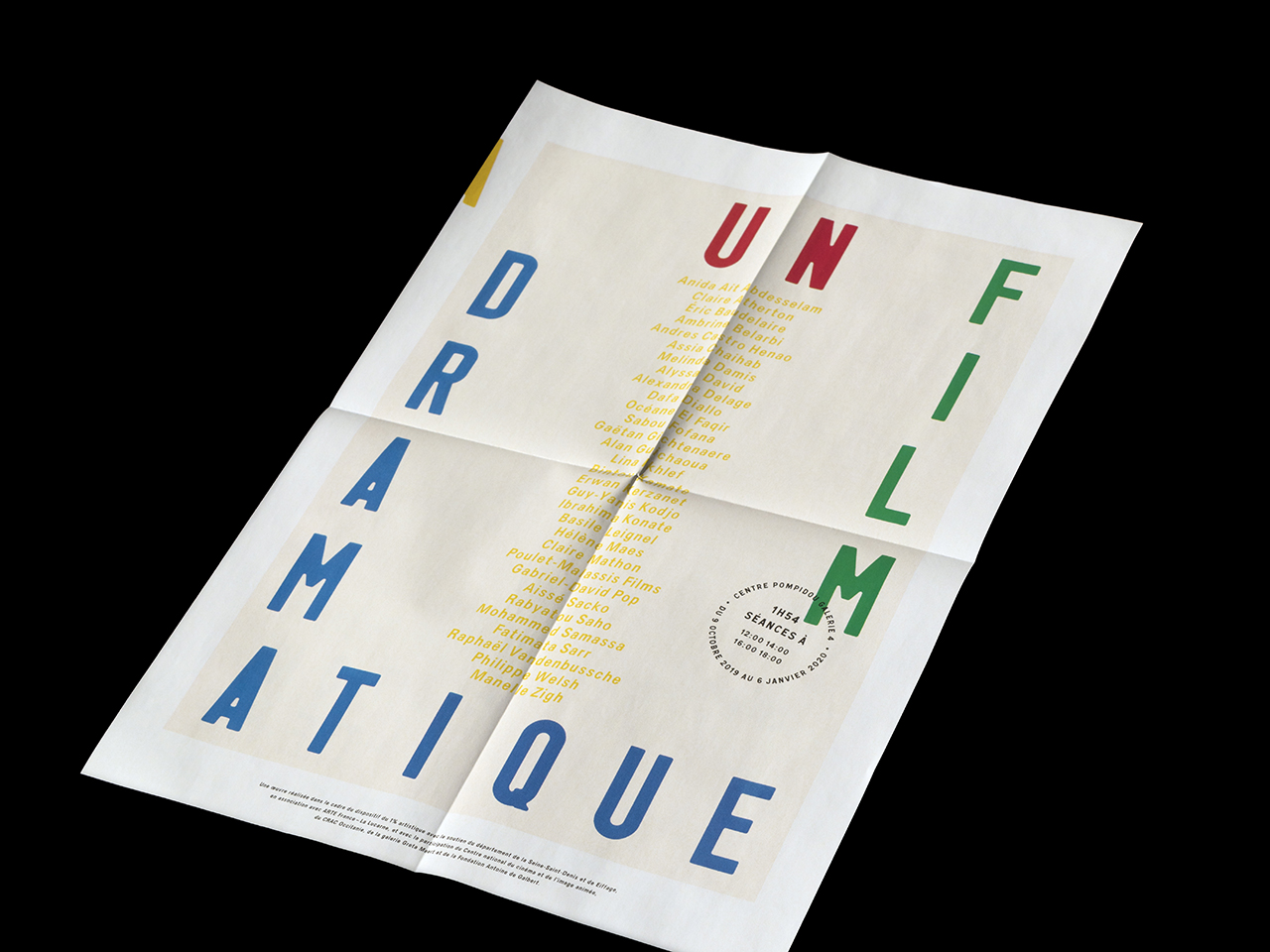

Installation in three parts presented for the 2019 Marcel Duchamp prize

October 9, 2019–January 6, 2020

Centre Pompidou, Paris

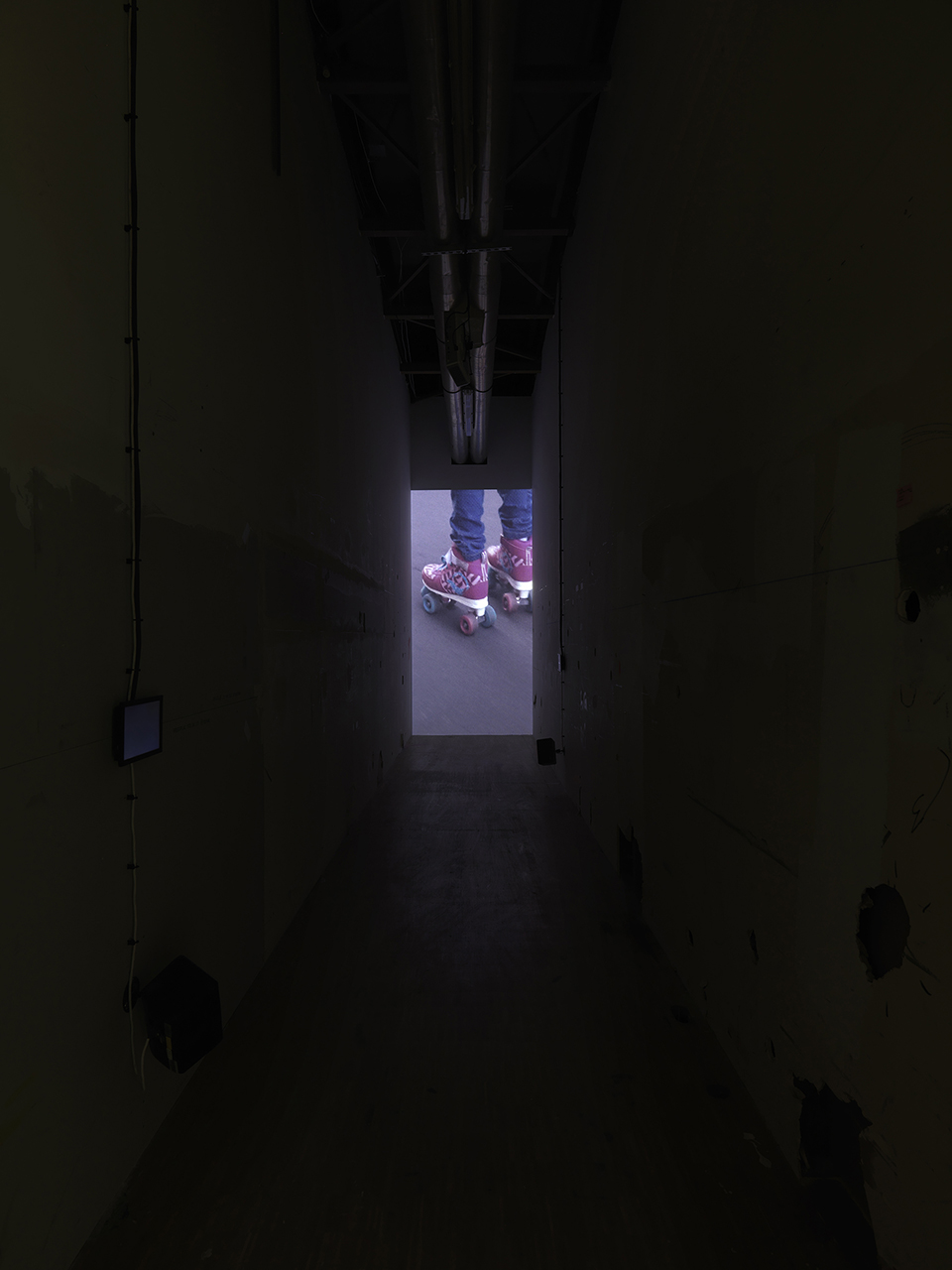

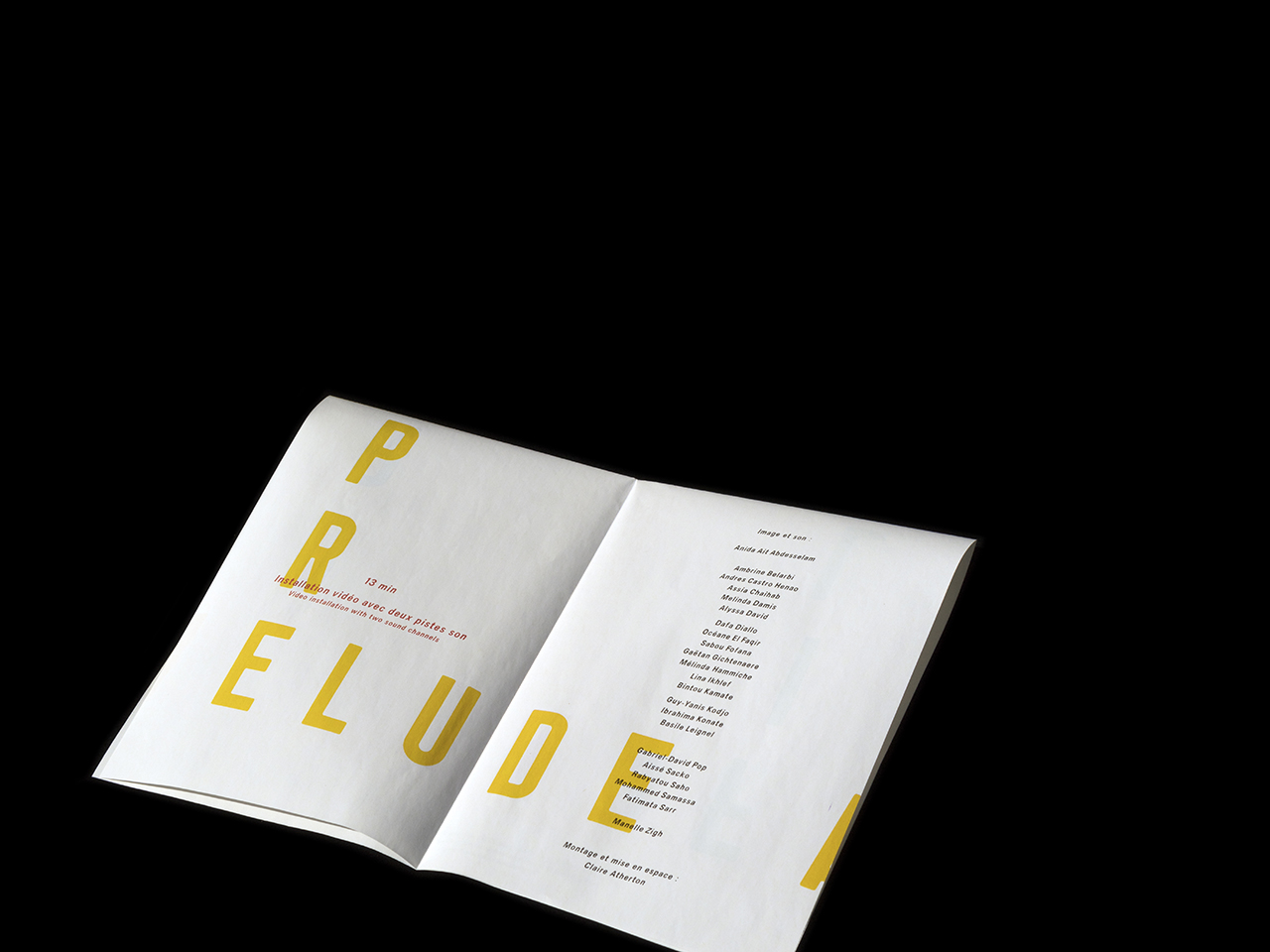

I. Prelude

Video installation, two sound chanels

13 minutes

II. Un film dramatique

HD video, stereo sound

114 minutes

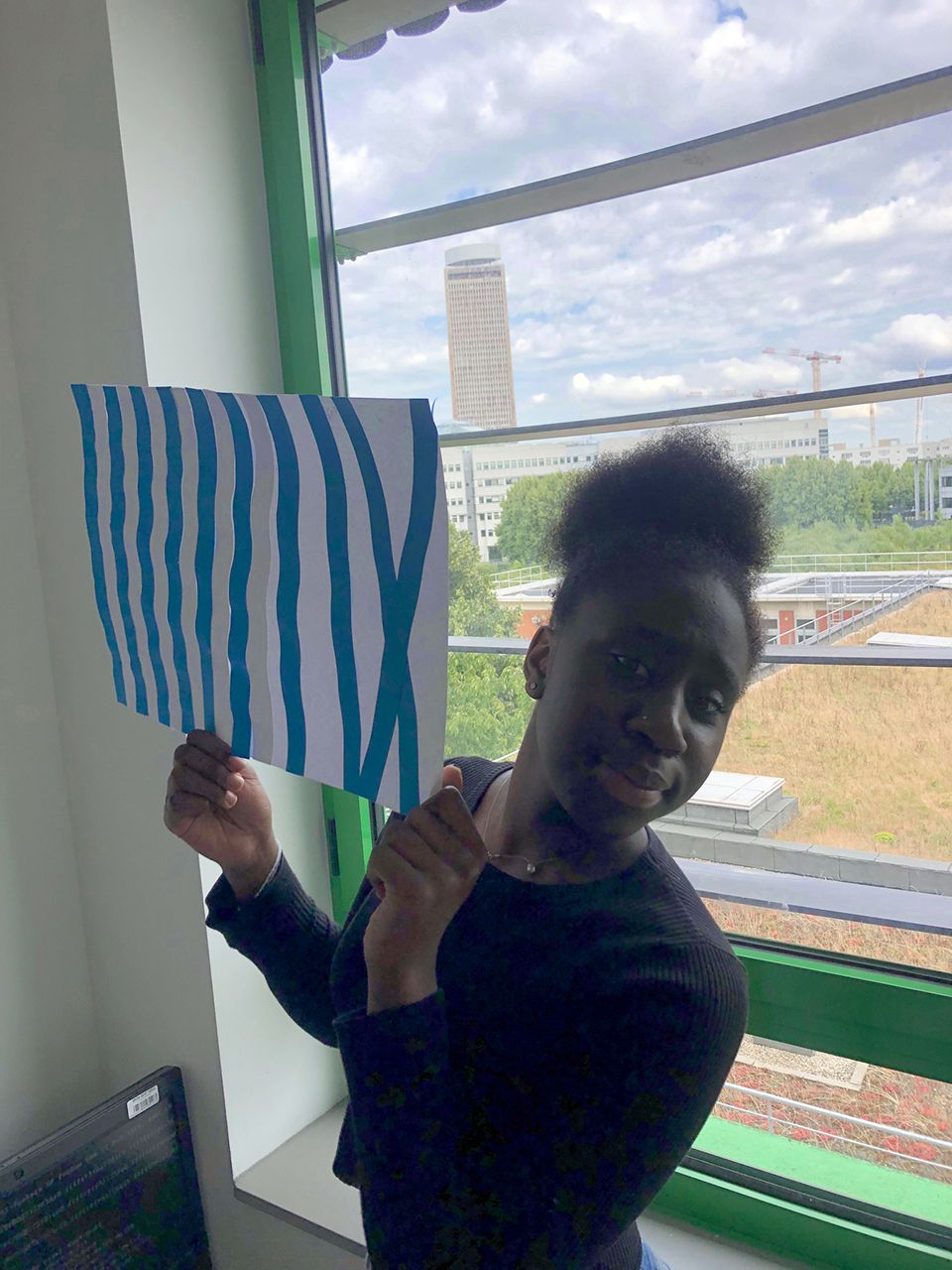

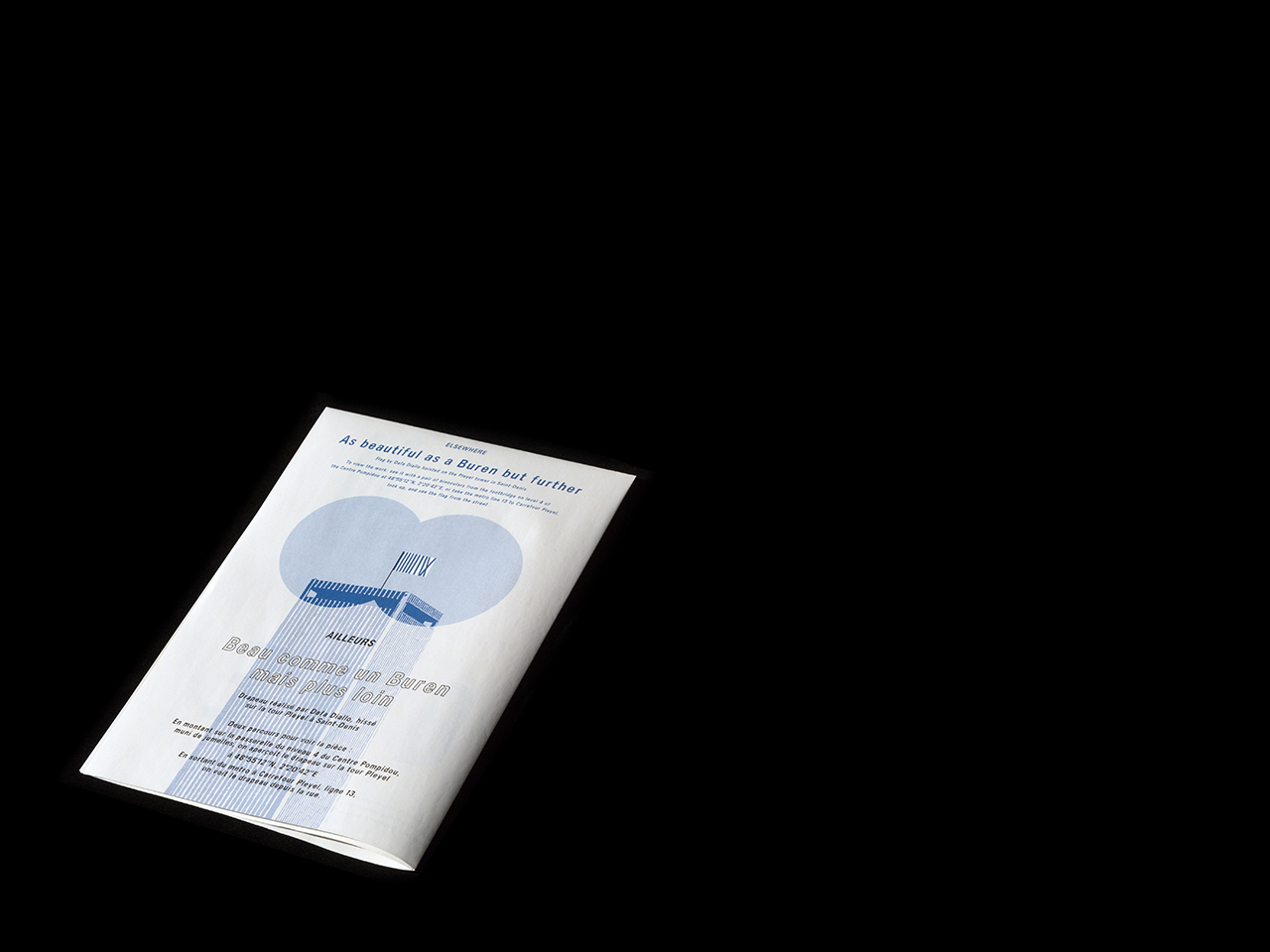

III. Beau comme un Buren mais plus loin [As Beautiful as a Buren but Further]

Flag designed by Dafa Diallo hoisted on the Pleyel tower in Saint-Denis

Printed matter, A5/A3 ︎︎︎

Philippe Mangeot

The title of Éric Baudelaire’s installation Tu peux prendre ton temps [You can take your time] was initially borrowed from one of the three works that composes it. In Un film dramatique, the young Fatimata instructs the person holding the camera to take her time and prolong her shot.

But Baudelaire has made the liberation of forms or images (and the intelligible possibilities that stem from it), one of his modus operandi. “You can take your time” is also addressed to us as we get ready to watch the 114 minute long film, preceded by the 13 minute Prélude – its black box, projected in a service corridor of the exhibition space. And you’ll have to take time again when you go to Saint-Denis to look at the flag (a reference to Buren) hoisted atop the Pleyel tower by the artist and a group of students from the Dora Maar middle school, which we have met in the previous two works. The museum has become a point of departure towards their world.

If you take your time, you’ll discover that the title of the installation is also the key to its creation. The filming of Un film dramatique lasted four years, during which Baudelaire regularly got together with the children he had first met when they entered the 6th grade.

Four years: enough time to watch their bodies grow, their voices break, their discourse develop or dwindle, and a past build up. It was also time enough for the school, filmed in-between classes, to do its work, and see the effects of the knowledge it generates within the students in the film itself. It was a time broken up by events that shook their lives, starting with the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks that altered the way their bodies were perceived in the immediate aftermath.

In all these ways, four years was a time of creation. Baudelaire and the students at Dora Maar never stopped asking themselves what it is they are making together. Answering this political question – one that involves representations of power, social violence and identity – led them to seek a cinematic form that does justice to the uniqueness of each student, but also to the substance of their group. What are we making together, if it is neither documentary nor fiction? A dramatic film, perhaps, where we discover the possibility for each to speak in their own name by filming for others, and to become co-authors of the film and subjects of their own lives.

We are therefore not surprised that the name of the artist figures without any special treatment in the credits, just the same as the names of all the children and the film’s editor Claire Atherton. In this regard, Baudelaire circles back to two questions which have been at the heart of his artistic journey up until now. The question of the author, a crisis he joyfully contributes to: virtually all of his work reveals a process whereby the subject of the work becomes part and parcel of its creation, to the extent that we could hypothesise that Éric Baudelaire is actually the name of a collective artist with shifting configurations. The second is the question of the construction of political subjectivities, which he explored in several films by borrowing Masao Adachi’s “landscape theory”: a good way of understanding someone is to look at what they see.

Here, Baudelaire radicalises the key themes in his work. He is no longer concerned with working with peers nor with people invested with the authority of knowledge, or a history. He is collaborating with youths who do not have a body of work or an archive of their pasts. Having entered the art world as a photographer orchestrating grand forms, Baudelaire now welcomes the erratic images produced by children as if they were his own.

Watching these children at work, it is hard to forget that they belong to the first generation to have always lived with a planetary catastrophe on the horizon. It was therefore inevitable that the threat of extinction would affect the very forms of art, redefining its ethical and aesthetic coordinates. By treating these children equally, by producing together a work whose ambition itself is rooted in its modesty, Baudelaire recognises this new order and leaves room for hope somewhere at the heart of these catastrophic thoughts, a hope that resides in this time we have left to take • Published in the exhibition catalog Le prix Marcel Duchamp 2019, Ed. Silvana Editoriale