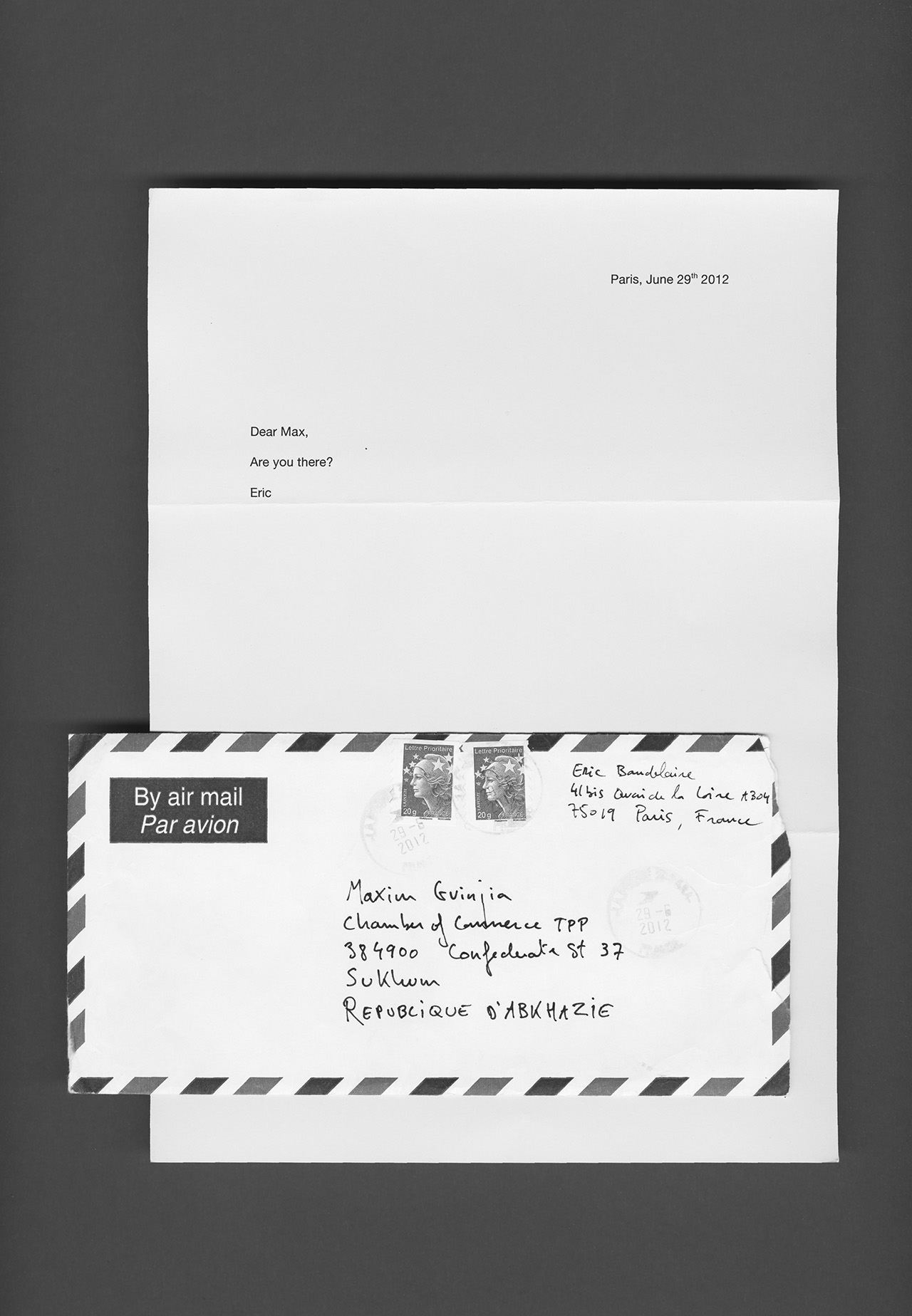

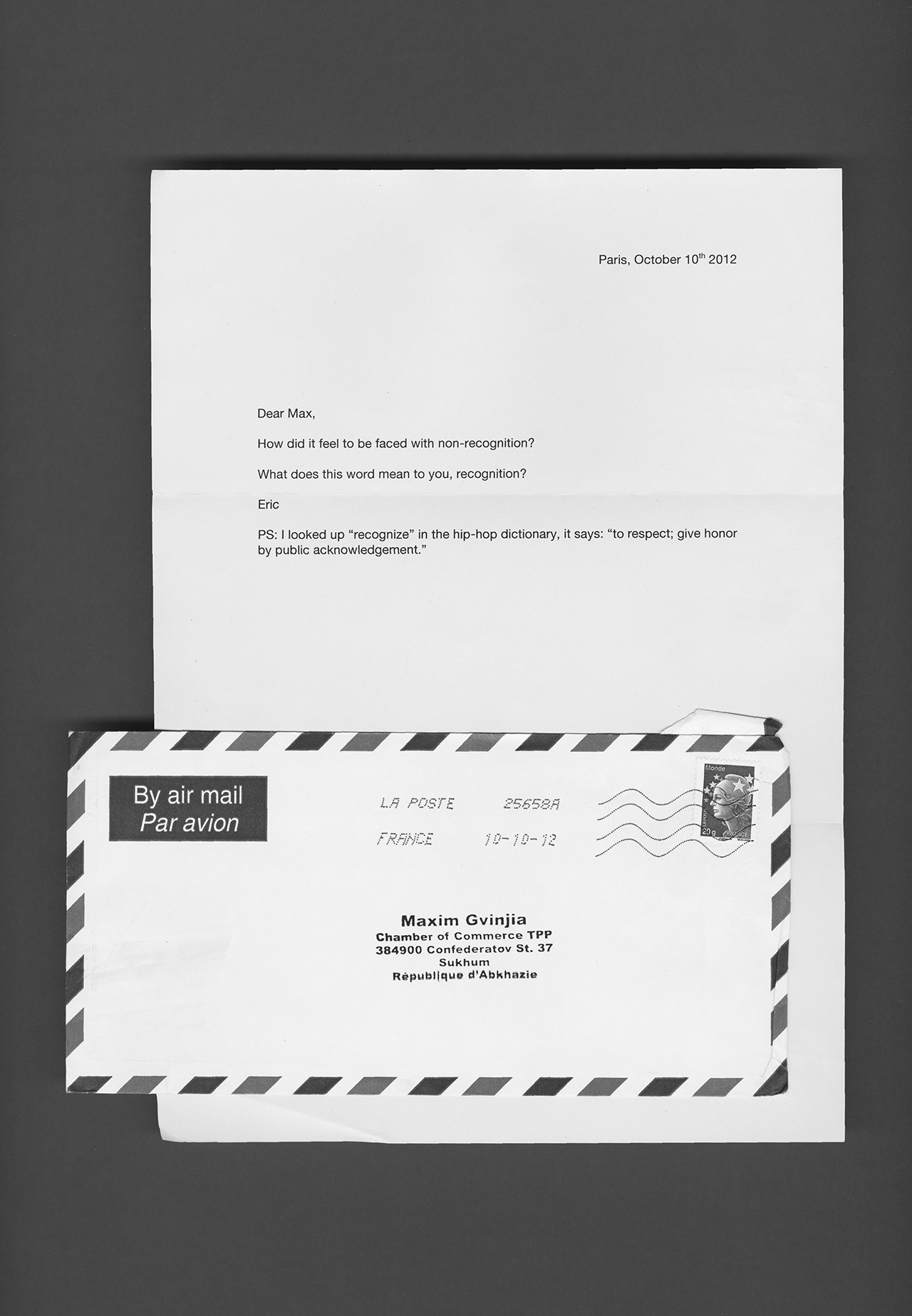

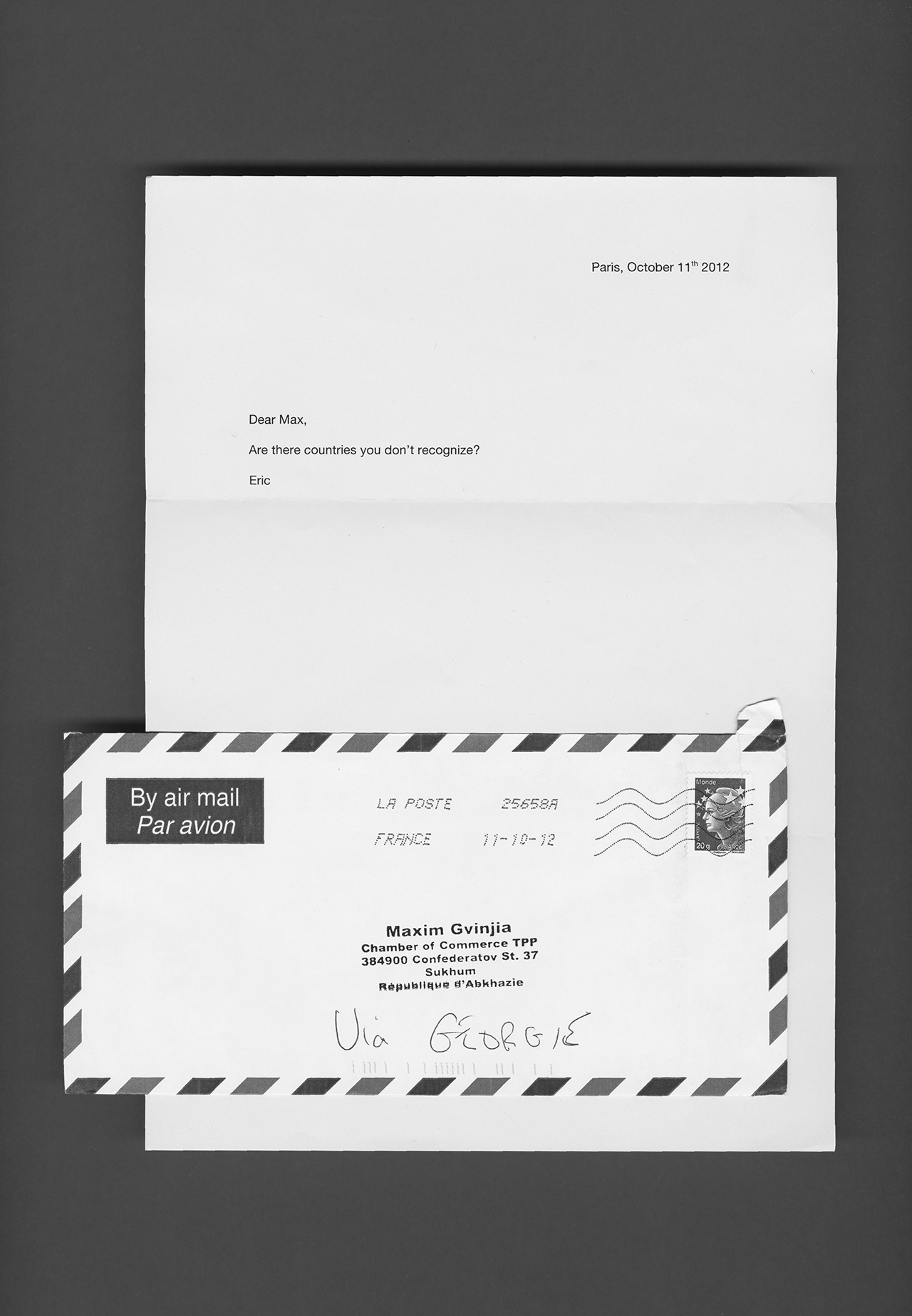

Abkhazia is something of a paradox: a country that exists, in the physical sense of the word (a territory with borders, a government, a flag and a language), yet it has no legal existence because for almost twenty years it was not recognized by any other nation state. Abkhazia exists without existing, caught in a liminal space, a space in between realities − which is why my first letter to Max was something of a message in a bottle thrown at sea.

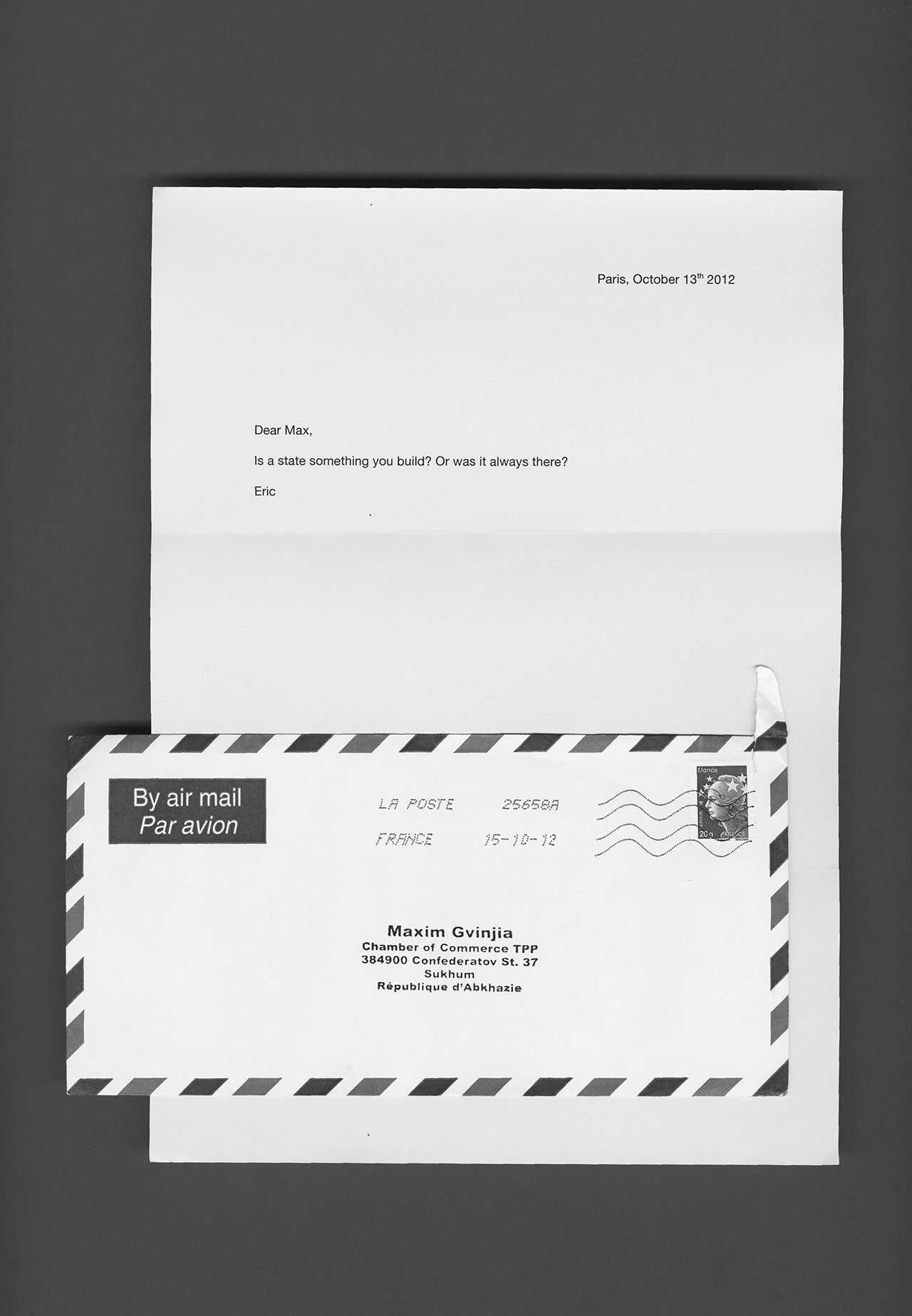

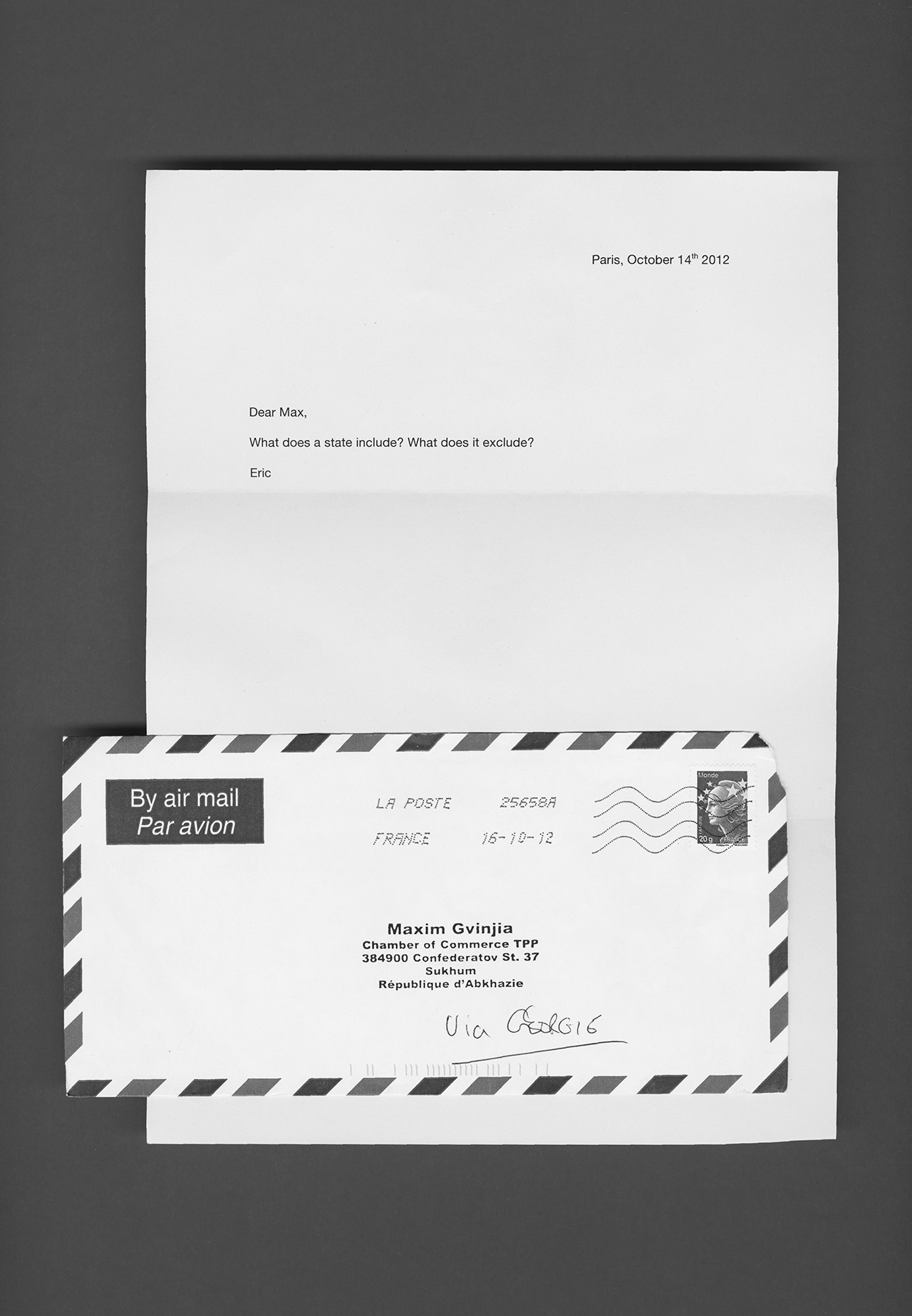

The existence of Abkhazia invites all kinds of questions. How do you build a new state? Is the idea of the state based on inclusion or exclusion? On what criteria can a state be considered to exist, and what forms of representation allow, or prove, this existence to be real? If all states are fictional collective constructs, what to make of Abkhazia: a fiction within a fiction?

Abkhazia seceded from Georgia after a civil war fought in 1992−1993. Like all disputed lands, Abkhazia is entangled in a conflicted narrative. To many Georgians, the breakaway state is a rogue nationalist regime, an amputated part of Georgia. To many Abkhaz, independence saved them from cultural extinction after years of Stalinist repression and Georgian domination. To many observers, Abkhazia is simply a pawn in the Great Game Russia and the West have always played in the Caucasus. The Secession Sessions acknowledges these competing narratives and does not seek to write an impossible objective historiography. It does not parse, verify or document any competing claims to a land. The project starts with this observation: Abkhazia has had a territorial and human existence for twenty years, and yet it will in all likelihood remain in limbo for the foreseeable future, which makes the self-construction of its narrative something worth exploring. If Abkhazia is a laboratory case for the birth of a nation, then its Giuseppe Garibaldis and George Washingtons are still alive and active. Maxim Gvinjia is one of them.

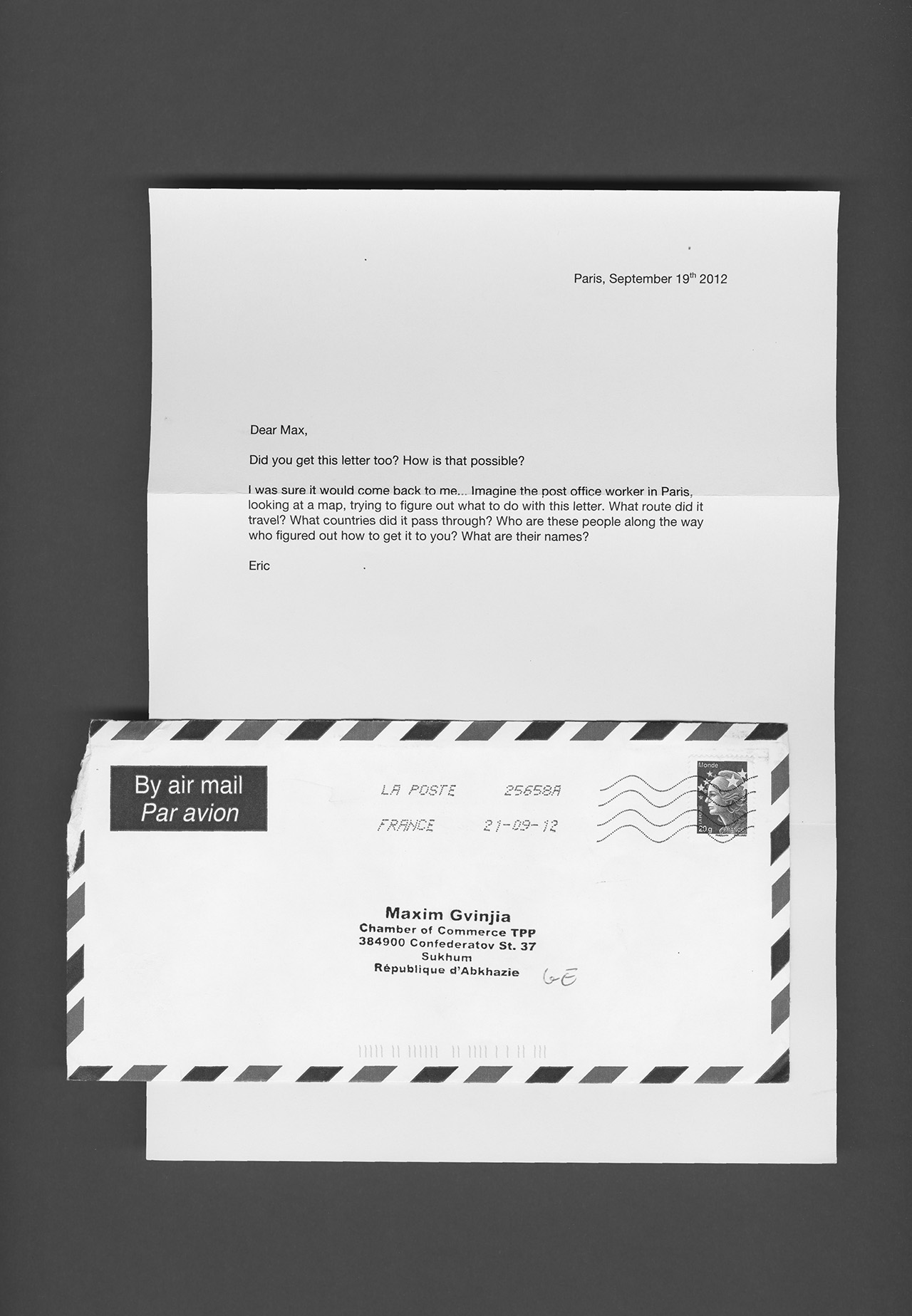

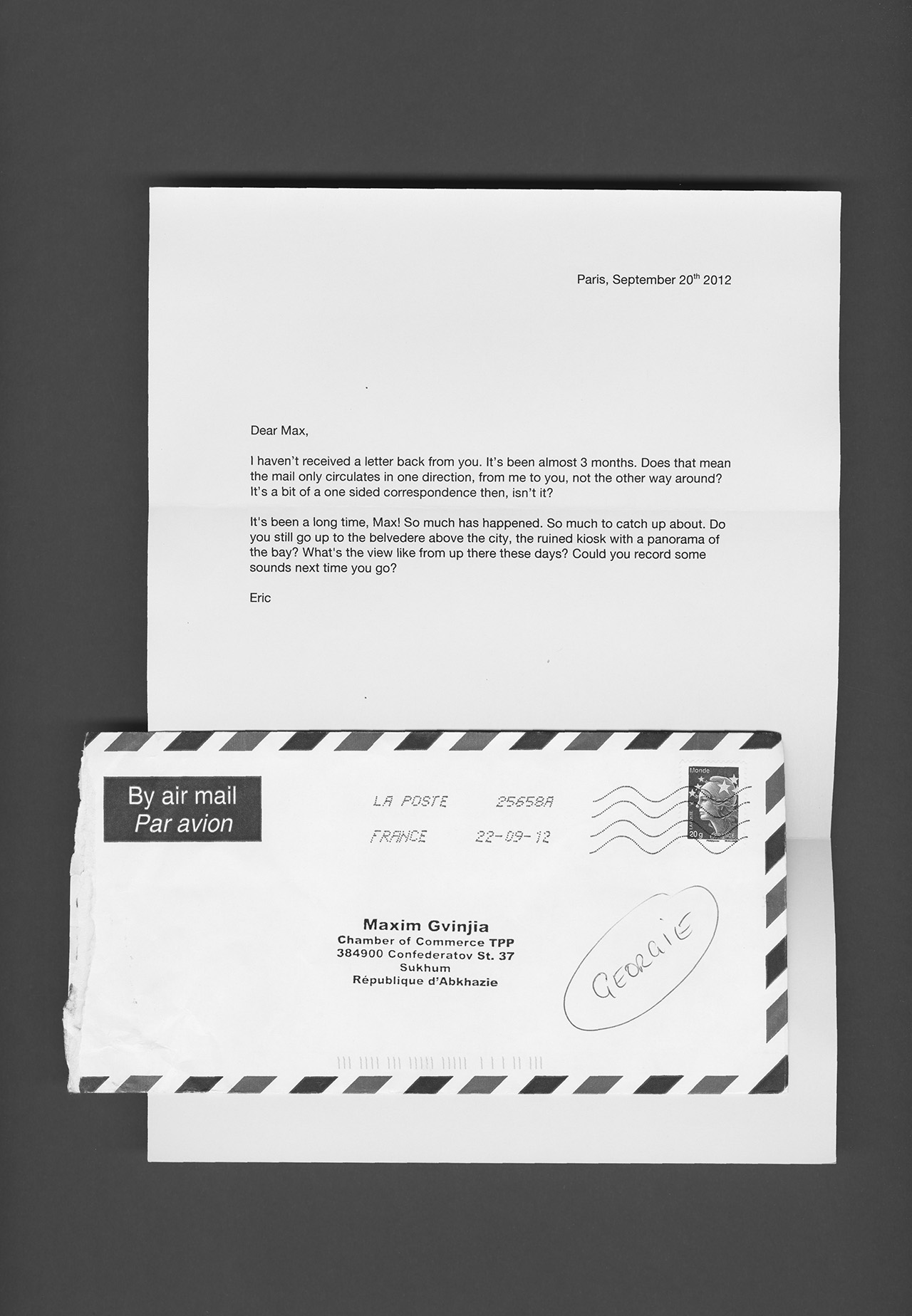

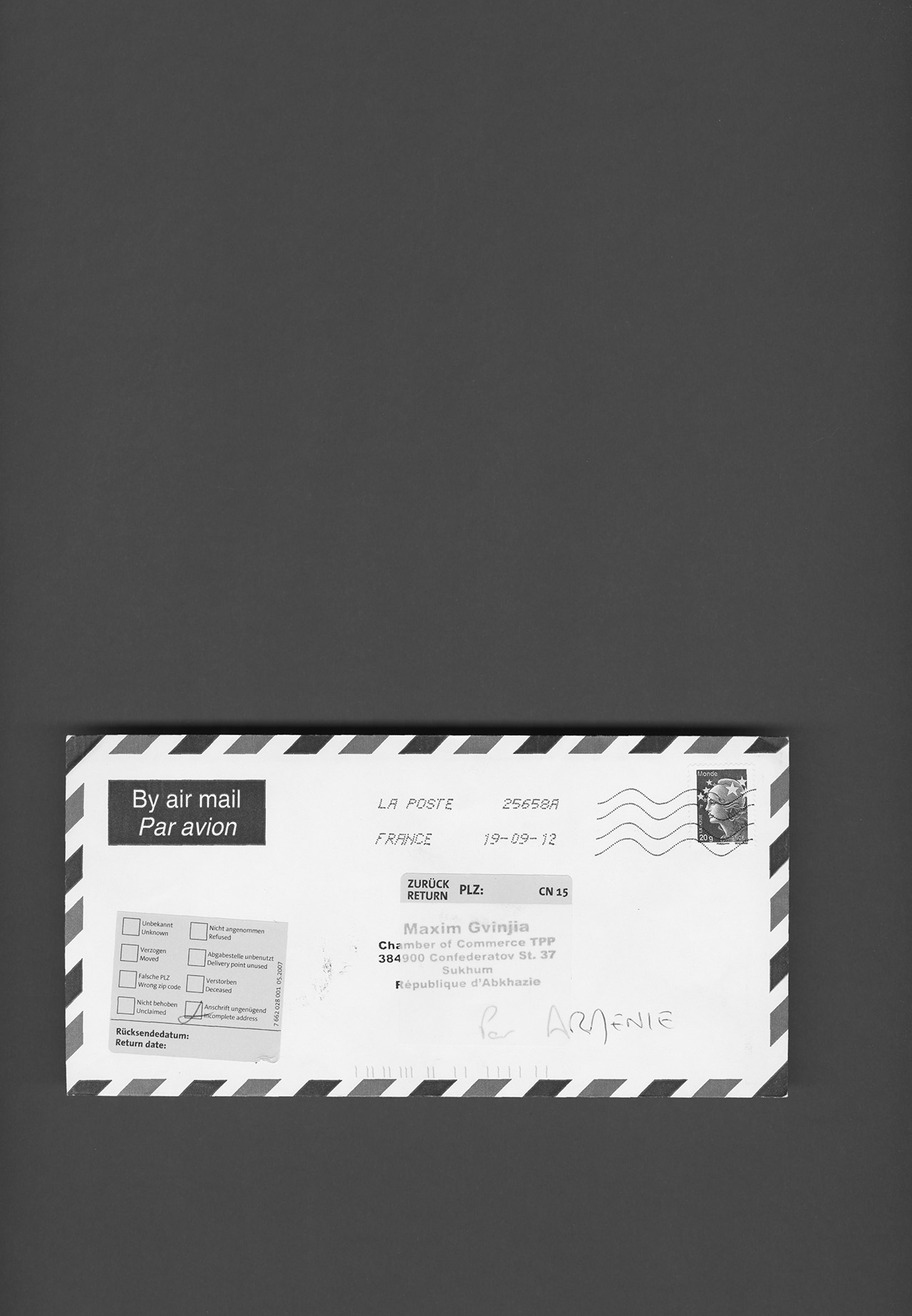

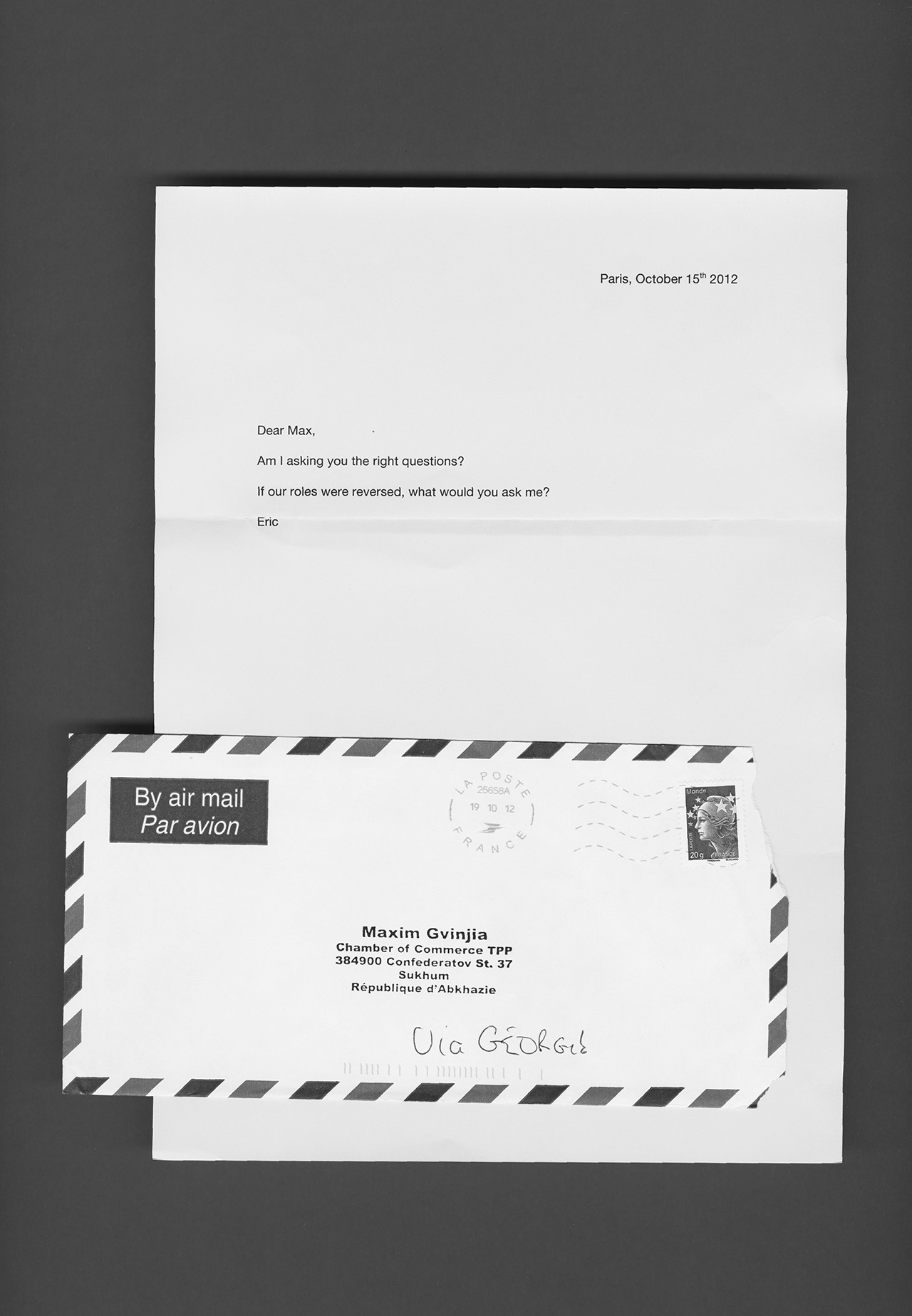

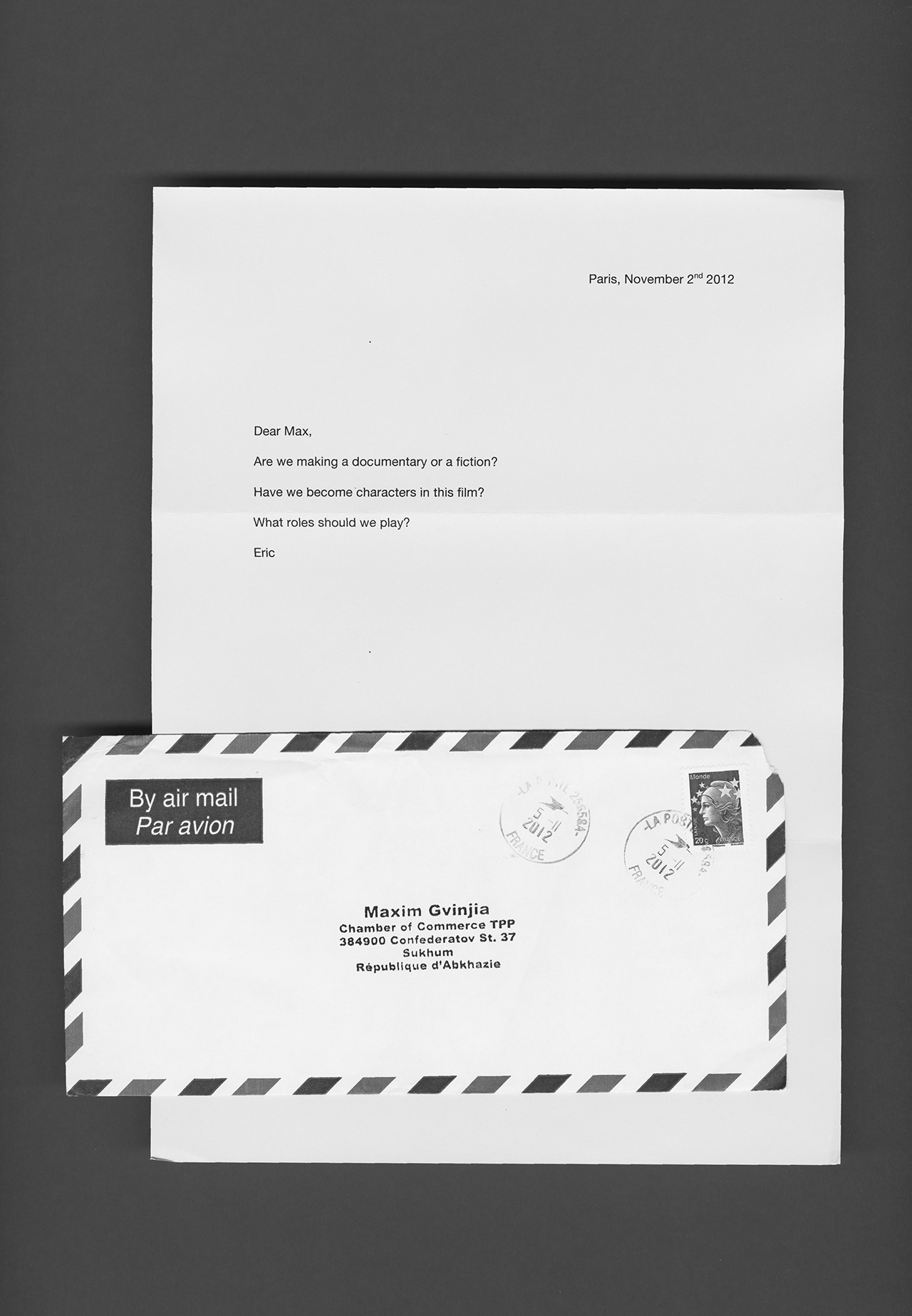

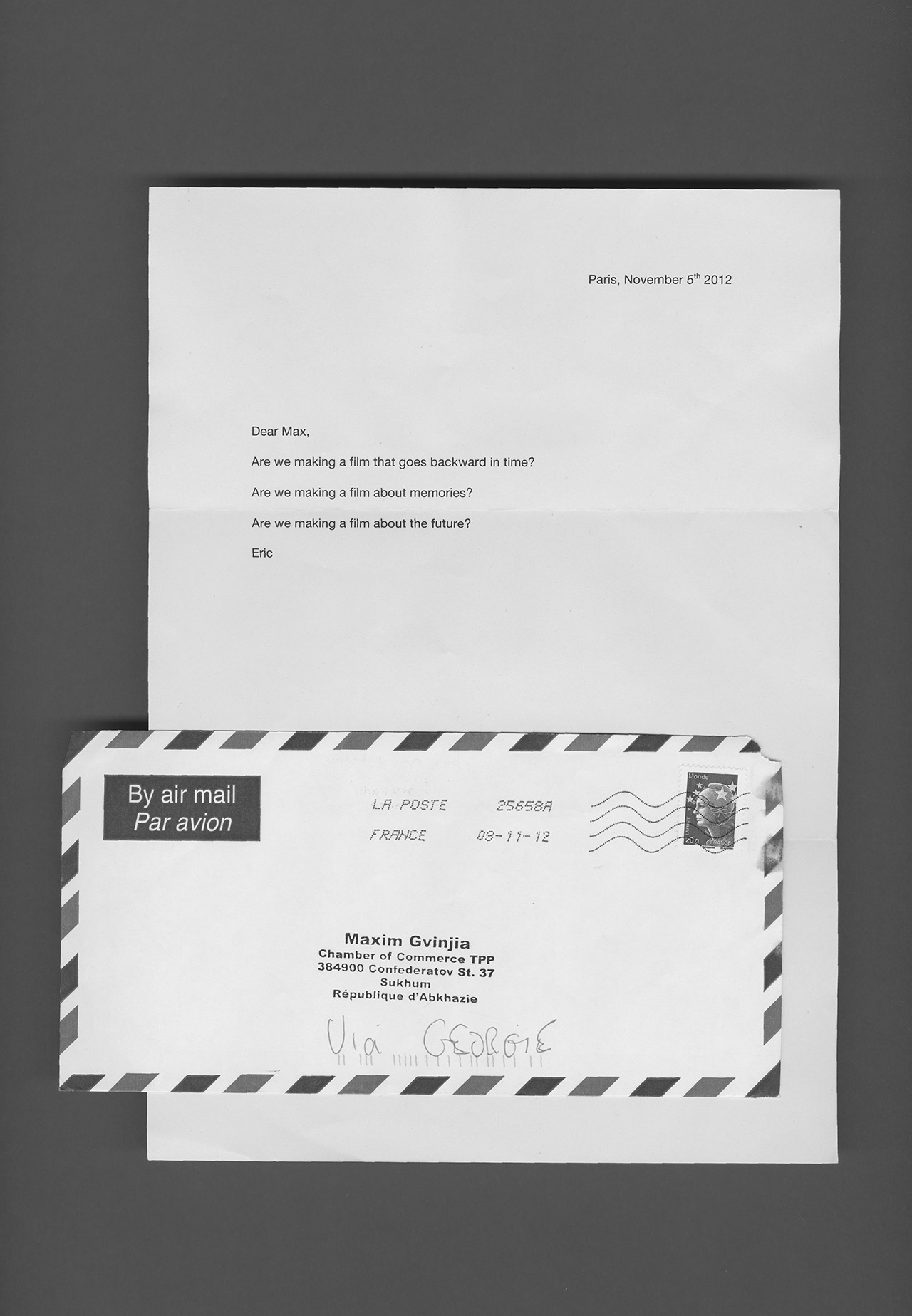

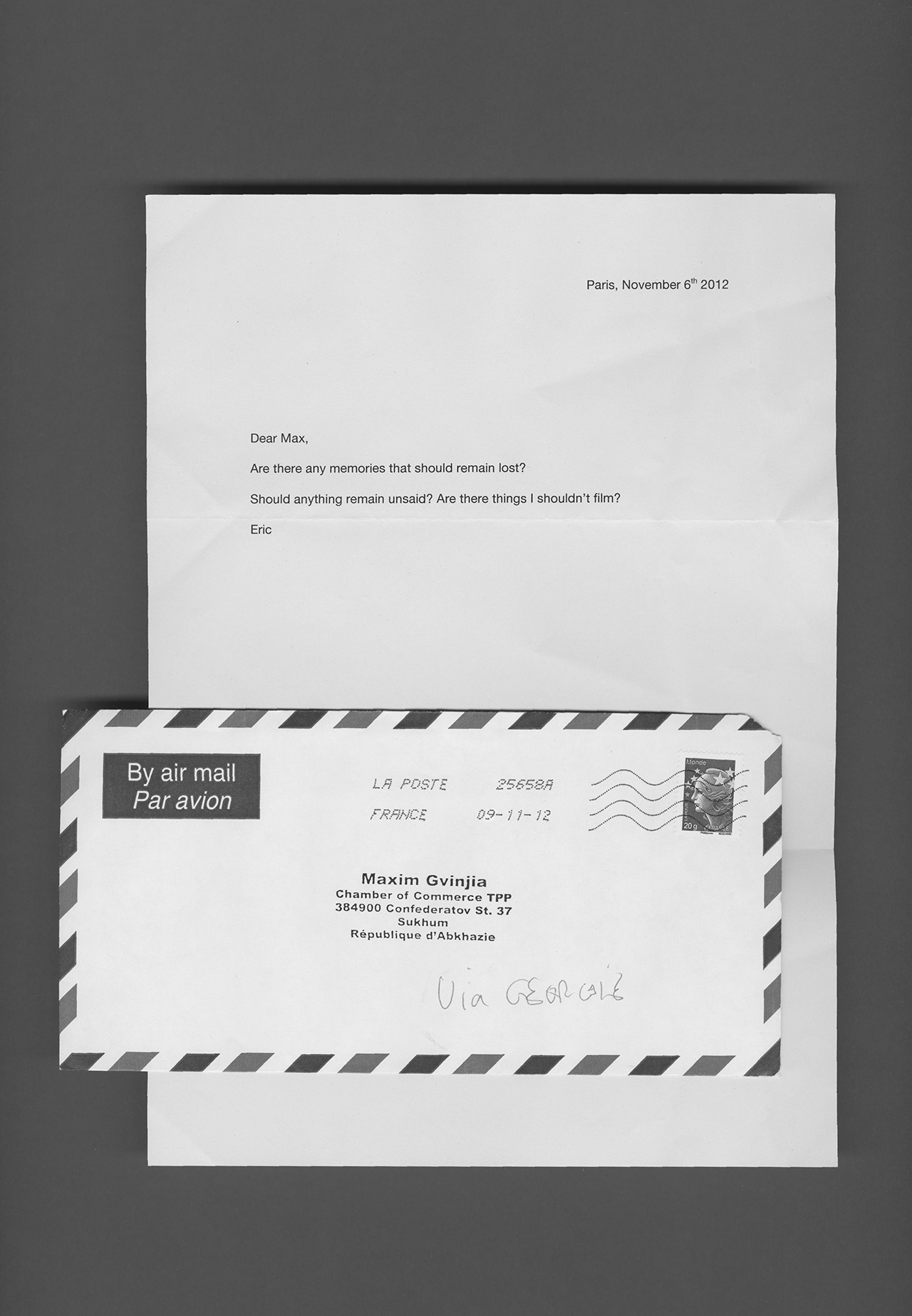

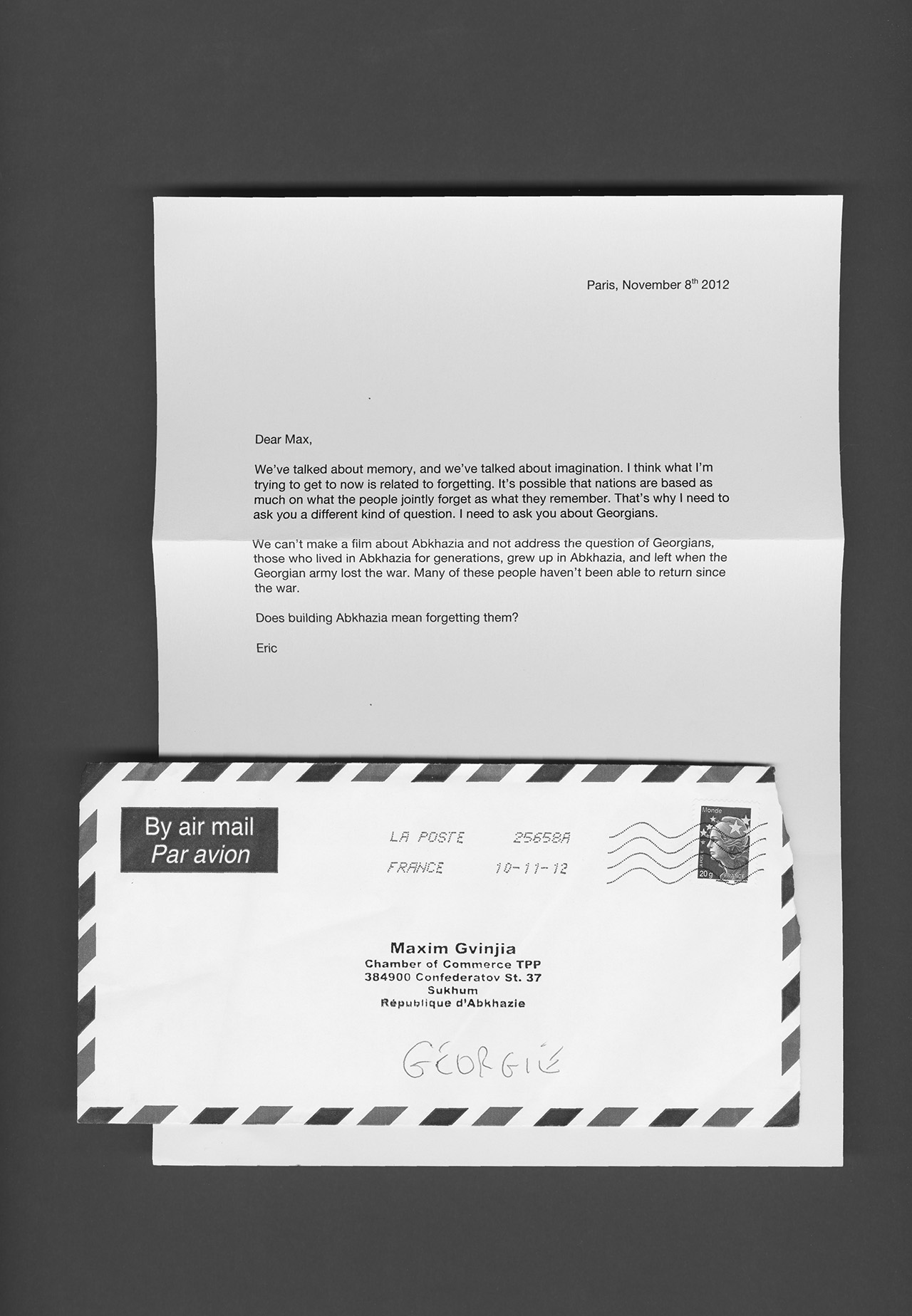

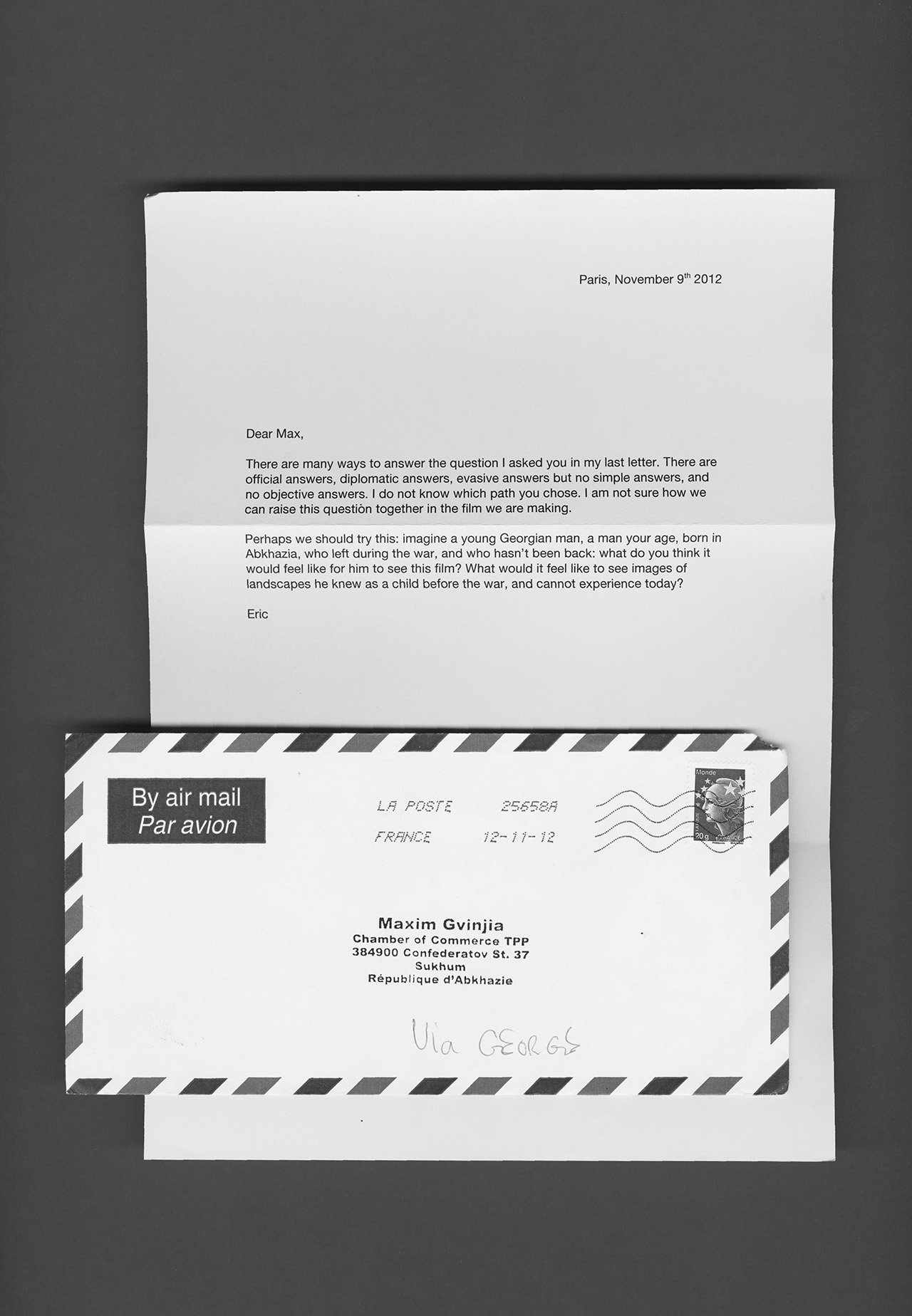

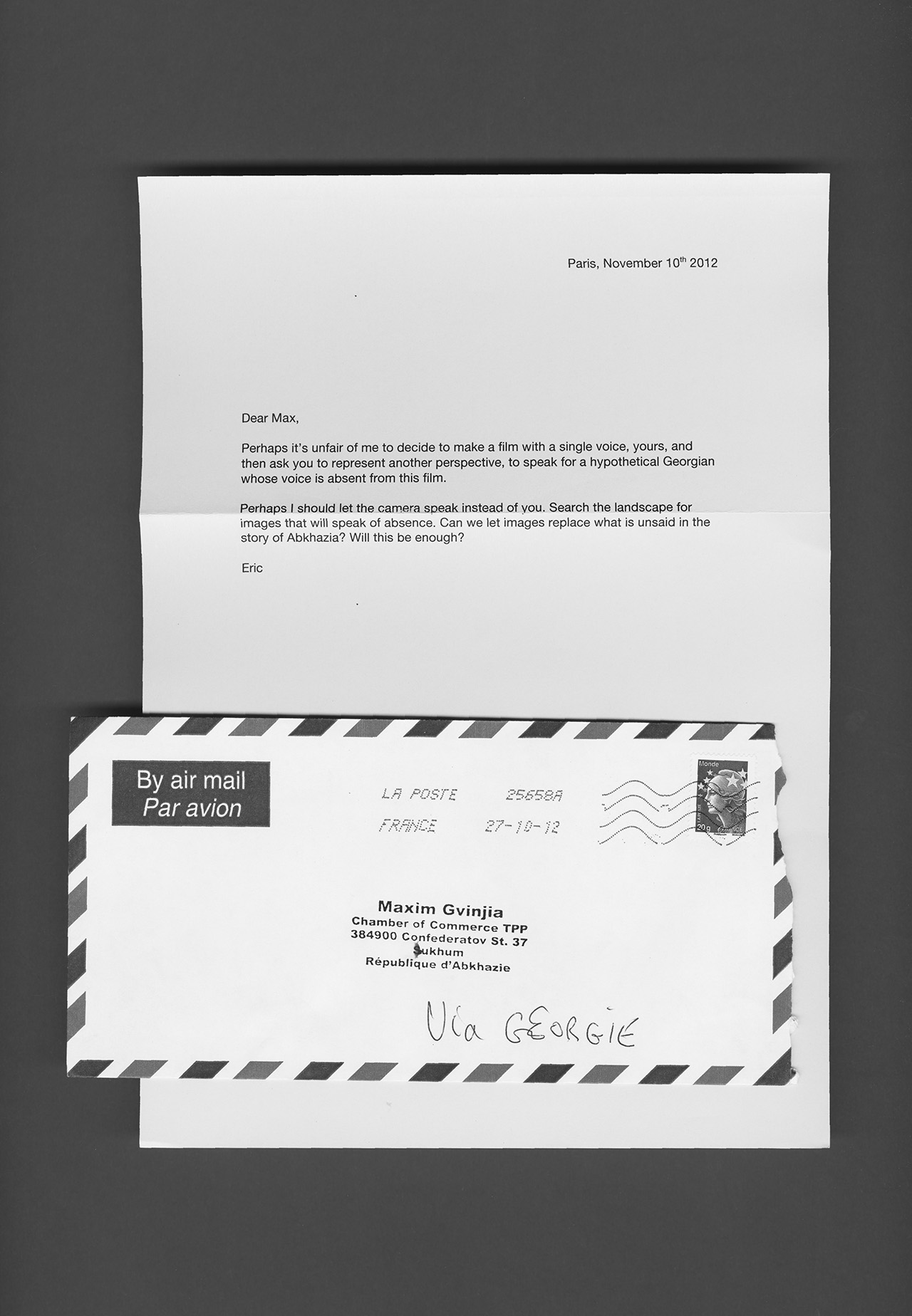

Back in June 2012, when I dropped the first envelope in a mailbox in Paris, I fully expected that a letter addressed to “Maxim Gvinjia, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sukhum, Republic of Abkhazia,” would come straight back to my studio with a notice from the post office marked “destination unknown.” But instead, to my surprise, ten weeks later I received an email from Max telling me he had received my letter, but could not reply on paper since the post office in Abkhazia cannot handle international mail. Instead, Max said he would speak his answers into a voice recorder. In September 2013, I went to visit Max in Abkhazia, and while listening to his recorded answers to my letters, I shot images for a film we had decided to make together • From the program for The Secession Sessions at Bétonsalon, 2014

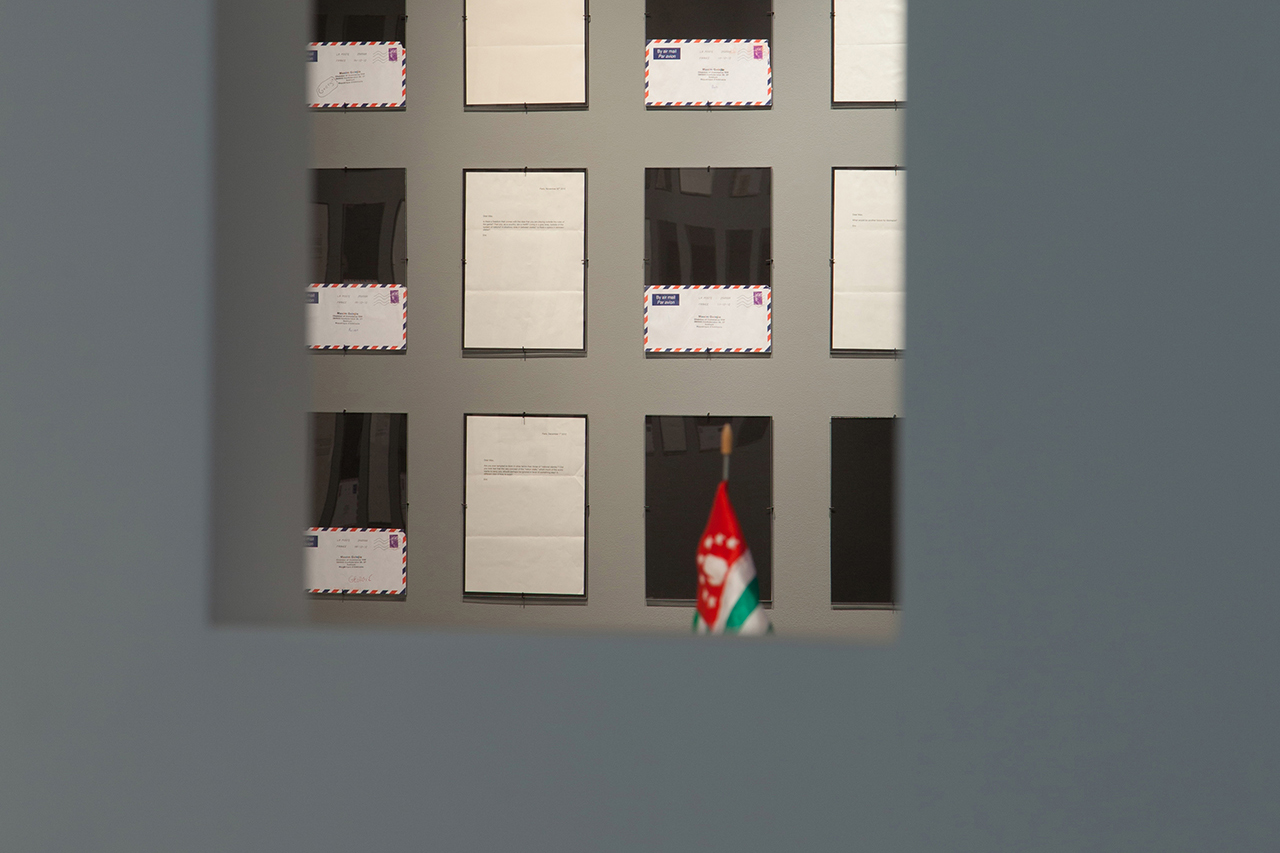

Those That Arrived and Some That Were Lost

74 letters, a one-sided correspondence that eventually became the script for a film

74 letters, a one-sided correspondence that eventually became the script for a film

The Anembassy of Abkhazia

built temporarily within the exhibition space and staffed by Maxim Gvinjia, former Foreign Minister of Abkhazia

built temporarily within the exhibition space and staffed by Maxim Gvinjia, former Foreign Minister of Abkhazia

The Sessions

a series of public programmes, talks and discussions held in the exhibition space at regular intervals for the duration of the show. Each programme is site specific and developed in partnership with the hosting institution

a series of public programmes, talks and discussions held in the exhibition space at regular intervals for the duration of the show. Each programme is site specific and developed in partnership with the hosting institution

The Secession Sessions have been held in the following cities since 2014:

January 9–March 8, 2014

The Secession Sessions

Bétonsalon, Centre d’Art et de Recherches, Paris

WEEKLY PUBLIC SESSIONS

Reinventing the State?

A conversation between Alain Badiou and Pierre Zaoui

The old Leviathans of the modern era, authoritarian and oppressive, were not particularly pleasant. But neither is the neo-liberal ideology of “always less State” for the benefit of the markets. Particularly as both of these political forms, the authoritarian State and economic liberalism, easily conjoin. Rather than dwelling on the same clichés about the generalized crisis of the modern State, this meeting could however question the current possibilities to reinvent a new relationship with the State. Is it possible to conceive a State that genuinely emancipates, or is it only another utopia by “absolute dreamers” described by Marx? This debate could also provide an opportunity to examine Badiou’s work and political commitment as a whole: the question of the State revolutionary; the communist hypothesis; the revolution; the radical critic of democratic representation •

State Desire

A seminar by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Elena Sorokina

In international law, the reasons for non-independent entities to aspire to statehood are enumerated as follows: the notion of sovereignty and the desire for independence and self-determination are the aspirations which come first; the possibility of joining international organizations only open to independent states; and the prospect of being involved in foreign affairs and the right to use force in self-defense are equally important. But what fuels these desires, what kind of affects are involved, how are they generated and expressed? Collectively produced, the strife for recognition and sovereignty is a special kind of affect, usually clashing against strict international regulations and laws. The speakers invited will present their reflections and insights into a range of topics, from visual expression to fictional (re)construction • Audio of this session on R22

Identity Ploys and Dangerous Fictions

Hosted by the journal Vacarme

No one knows for sure what “identity” means, but all minorities most definitely need to fictionalize identities for themselves. To fictionalize is both to let the cat out of the bag and to hide, to resist the dominant order and accept its game, but to play it differently. Nevertheless when the identity trick becomes a national project and a desire for the State, it is continually at risk of falling into violent or sad re-territorializations. A group discussion moderated by Vacarme on the intersection of fictions, the politics of emancipation, the relation to the State and the rise of European fascisms • Audio of this session on R22

The Nitty Gritty of the State

A lecture by Fabien Jobard

The State, as we say, is the monopoly of violence. The State, it seems, is primarily the army, the police, and prison. But taking a closer look, the State is above all an edifice made of papers. It draws its legitimacy from a written Constitution, and not anymore from customary or divine law. This document, and the seals that attest it, are kept precisely by the same ministry that manages sentences and prisons. The State and its agents dispose of an authority, of a power that is first and foremost made of paper. From a research conducted in Paris on police identity checks, this very particular act which entails the identification of individuals thanks to their papers by depository agents of the public authority, we offer to enlighten the establishment of the State grasped in History and the consistency of papers that link individuals to public authority. Having papers. Having one’s papers. Losing one’s papers. Presenting them. Is this really how we make the State? • Audio of this session on R22

Exhibition libretto︎︎︎

The Secession Sessions

Bétonsalon, Centre d’Art et de Recherches, Paris

WEEKLY PUBLIC SESSIONS

Reinventing the State?

A conversation between Alain Badiou and Pierre Zaoui

The old Leviathans of the modern era, authoritarian and oppressive, were not particularly pleasant. But neither is the neo-liberal ideology of “always less State” for the benefit of the markets. Particularly as both of these political forms, the authoritarian State and economic liberalism, easily conjoin. Rather than dwelling on the same clichés about the generalized crisis of the modern State, this meeting could however question the current possibilities to reinvent a new relationship with the State. Is it possible to conceive a State that genuinely emancipates, or is it only another utopia by “absolute dreamers” described by Marx? This debate could also provide an opportunity to examine Badiou’s work and political commitment as a whole: the question of the State revolutionary; the communist hypothesis; the revolution; the radical critic of democratic representation •

State Desire

A seminar by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Elena Sorokina

In international law, the reasons for non-independent entities to aspire to statehood are enumerated as follows: the notion of sovereignty and the desire for independence and self-determination are the aspirations which come first; the possibility of joining international organizations only open to independent states; and the prospect of being involved in foreign affairs and the right to use force in self-defense are equally important. But what fuels these desires, what kind of affects are involved, how are they generated and expressed? Collectively produced, the strife for recognition and sovereignty is a special kind of affect, usually clashing against strict international regulations and laws. The speakers invited will present their reflections and insights into a range of topics, from visual expression to fictional (re)construction • Audio of this session on R22

Identity Ploys and Dangerous Fictions

Hosted by the journal Vacarme

No one knows for sure what “identity” means, but all minorities most definitely need to fictionalize identities for themselves. To fictionalize is both to let the cat out of the bag and to hide, to resist the dominant order and accept its game, but to play it differently. Nevertheless when the identity trick becomes a national project and a desire for the State, it is continually at risk of falling into violent or sad re-territorializations. A group discussion moderated by Vacarme on the intersection of fictions, the politics of emancipation, the relation to the State and the rise of European fascisms • Audio of this session on R22

The Nitty Gritty of the State

A lecture by Fabien Jobard

The State, as we say, is the monopoly of violence. The State, it seems, is primarily the army, the police, and prison. But taking a closer look, the State is above all an edifice made of papers. It draws its legitimacy from a written Constitution, and not anymore from customary or divine law. This document, and the seals that attest it, are kept precisely by the same ministry that manages sentences and prisons. The State and its agents dispose of an authority, of a power that is first and foremost made of paper. From a research conducted in Paris on police identity checks, this very particular act which entails the identification of individuals thanks to their papers by depository agents of the public authority, we offer to enlighten the establishment of the State grasped in History and the consistency of papers that link individuals to public authority. Having papers. Having one’s papers. Losing one’s papers. Presenting them. Is this really how we make the State? • Audio of this session on R22

Exhibition libretto︎︎︎

February 4–21 , 2015

The Secession Sessions

Matrix 257, UC Berkeley Art Museum - BAM/PFA and Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco (Curated by Apsara DiQuinzio)

WEEKLY PUBLIC SESSIONS

Secession Made in USA

With members of the Cascadia Independence Movement and Joshua Clover

Donetsk, Kurdistan, Abkhazia, Kosovo… Separatism is usually portrayed as a troublesome yet distant question of foreign affairs, but the issue of secession also has a deep-rooted, homegrown, American tradition. From Aaron Burr to the Confederate states to black separatist movements, many have questioned the integrity of the American federation in speech and in deeds. For this second session, we invite representatives from the Cascadia independence movement to make their case for secession, while theorist Joshua Clover will argue for a complete reframing of the question of Secession Made in USA in the age of globalization • Video documentation of this session (part one + part two)

Performance as Politics and Vice Versa

With Julia Bryan-Wilson, David Buuck, Aaron Gach

This session explores the convergence between political activism and performance art. Julia Bryan-Wilson will weave a brief history of artists adopting/highjacking/transforming the structures, symbols, or rituals of political systems; re-creating political systems within their practices; or building social projects as performance art. Aaron Gach will talk about his work and the Center for Tactical Magic, a fusion force summoned from the ways of the artist, the magician, the ninja, and the private investigator. And David Buuck will lecture/perform on how artists and activists have attempted to puncture holes in the state apparatus, in moments of refusal or withdrawal • Video documentation of this session

Georgian Voices

With Harsha Ram and guests

In his forty-eighth letter to Max, Éric wrote: “Perhaps it’s unfair of me to decide to make a film with a single voice, yours, and then ask you to represent another perspective, to speak for a hypothetical Georgian whose voice is absent from this film. Perhaps I should let the camera speak instead of you. Search the landscape for images that will speak of absence. Can we let images replace what is unsaid in the story of Abkhazia? Will this be enough?” In this session, Harsha Ram invites members from the Georgian community in the Bay Area to reflect on this question and discuss the issue of voice and representation in the conflicting narratives of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict • Video documentation of this session

Present Future of Emancipation

Martin Jay and Tarek Elhaik

In this session, Martin Jay and Tarek Elhaik tackle the fundamental issues at play throughout The Secession Sessions and take them to their most critical horizon: the question of emancipation.

How can we be free, living in the community of our choice, according to rules we fashion, in dignity and equality? Nationalism was the nineteenth-century answer to this question of emancipation, and the paradigm persisted within the postcolonial movements of the twentieth century. The result is a world of states, where every piece of the map has been divided up and flagged. Guided by the same answer, we see conflicts still raging in many parts of the world (Abkhazia is one of them). We see also the poverty of this way of thinking and acting in a world that is increasingly globalized (a dead-end on the road to nowhere?) and we witness the impossible coexistence of nationalist aspirations on a map where ethnic and cultural boundaries do not match the demarcations of existing states, and never will. What is the present future of emancipation in the twenty-first century? What alternatives are there to nationalism and the state? Does nonterritorial emancipation have any meaning in a world of states? Must emancipation always be grounded in territory to have lasting power? Can individual emancipation provide real answers that are meaningful at the community level? Can we imagine new forms of emancipation? • Video documentation of this session

Exhibition libretto︎︎︎

The Secession Sessions

Matrix 257, UC Berkeley Art Museum - BAM/PFA and Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco (Curated by Apsara DiQuinzio)

WEEKLY PUBLIC SESSIONS

Secession Made in USA

With members of the Cascadia Independence Movement and Joshua Clover

Donetsk, Kurdistan, Abkhazia, Kosovo… Separatism is usually portrayed as a troublesome yet distant question of foreign affairs, but the issue of secession also has a deep-rooted, homegrown, American tradition. From Aaron Burr to the Confederate states to black separatist movements, many have questioned the integrity of the American federation in speech and in deeds. For this second session, we invite representatives from the Cascadia independence movement to make their case for secession, while theorist Joshua Clover will argue for a complete reframing of the question of Secession Made in USA in the age of globalization • Video documentation of this session (part one + part two)

Performance as Politics and Vice Versa

With Julia Bryan-Wilson, David Buuck, Aaron Gach

This session explores the convergence between political activism and performance art. Julia Bryan-Wilson will weave a brief history of artists adopting/highjacking/transforming the structures, symbols, or rituals of political systems; re-creating political systems within their practices; or building social projects as performance art. Aaron Gach will talk about his work and the Center for Tactical Magic, a fusion force summoned from the ways of the artist, the magician, the ninja, and the private investigator. And David Buuck will lecture/perform on how artists and activists have attempted to puncture holes in the state apparatus, in moments of refusal or withdrawal • Video documentation of this session

Georgian Voices

With Harsha Ram and guests

In his forty-eighth letter to Max, Éric wrote: “Perhaps it’s unfair of me to decide to make a film with a single voice, yours, and then ask you to represent another perspective, to speak for a hypothetical Georgian whose voice is absent from this film. Perhaps I should let the camera speak instead of you. Search the landscape for images that will speak of absence. Can we let images replace what is unsaid in the story of Abkhazia? Will this be enough?” In this session, Harsha Ram invites members from the Georgian community in the Bay Area to reflect on this question and discuss the issue of voice and representation in the conflicting narratives of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict • Video documentation of this session

Present Future of Emancipation

Martin Jay and Tarek Elhaik

In this session, Martin Jay and Tarek Elhaik tackle the fundamental issues at play throughout The Secession Sessions and take them to their most critical horizon: the question of emancipation.

How can we be free, living in the community of our choice, according to rules we fashion, in dignity and equality? Nationalism was the nineteenth-century answer to this question of emancipation, and the paradigm persisted within the postcolonial movements of the twentieth century. The result is a world of states, where every piece of the map has been divided up and flagged. Guided by the same answer, we see conflicts still raging in many parts of the world (Abkhazia is one of them). We see also the poverty of this way of thinking and acting in a world that is increasingly globalized (a dead-end on the road to nowhere?) and we witness the impossible coexistence of nationalist aspirations on a map where ethnic and cultural boundaries do not match the demarcations of existing states, and never will. What is the present future of emancipation in the twenty-first century? What alternatives are there to nationalism and the state? Does nonterritorial emancipation have any meaning in a world of states? Must emancipation always be grounded in territory to have lasting power? Can individual emancipation provide real answers that are meaningful at the community level? Can we imagine new forms of emancipation? • Video documentation of this session

Exhibition libretto︎︎︎

March 5–June 5, 2015

The Secession Sessions

Sharjah Biennial 12: The Past, the Present, the Possible, UAE (Curated by Eungie Joo)

Exhibition libretto︎︎︎

June 14–July 16, 2017

Reconstruction of Story: Polyphony, the Imaginary of 'I'

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, Korea

Reconstruction of Story: Polyphony, the Imaginary of 'I'

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, Korea

October 26–March 13, 2017

Territories and Fictions: Thinking a New Way of the World

Museo Nacional Centro Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Territories and Fictions: Thinking a New Way of the World

Museo Nacional Centro Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Rasha Salti in conversation with Éric Baudelaire, catalog of Sharjah Biennial 12

Rasha Salti: I never would have imagined that a film about nationalism (let alone separatist nationalism) could be so gentle and serene. Even before the last century ended, the ethnic origins of nationalism and the self-determination of ethnic or cultural minorities in multicultural nations had a vexed relationship with the regime of human rights. On the one hand, a number of conflicts resulting from the ill settlement of issues related to territorial sovereignty and ‘nation-states’ have endured since the end of the Second World War and the formal end of colonial mandates; and on the other hand, the breakdown of the Soviet empire resulted in the emergence of very small ethnocultural states in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. In Letters to Max (2014), the strident words and emotions that the subject usually incites are remarkably absent, perhaps because of your tangible affection for the place and its people. The subject nonetheless remains a minefield. I wonder if you could expand on your decision for the moment in the film where you evoke the question of ‘forgetting’ Georgians.

Éric Baudelaire: A conventional documentary would present the geopolitical landscape of the Abkhaz-Georgian dispute within its opening minutes. I was keen on inverting that expectation. Max, a soft-spoken, reasonable, charismatic character, is introduced first; a rapport with him develops; his personal history is heard; we see his poetic and unusual perspective on life. Then, very late in the film, we come to understand that his position, and indeed the overall position of Abkhazia as a de facto state, is largely built on the exclusion of Georgians from territory they’ve inhabited for generations. Max appears in a new light, and the viewers’ feelings about a lot of things already seen or heard in the film are reevaluated. Or are they? Can ambivalent feelings coexist? Like some of my previous projects, Letters to Max is based on the idea of abandoning objectivity as a functional concept in making work about particularly divisive topics, then in turn problematising subjectivity in ways that are insightful, that allow us to reexamine the framework of a given situation.

RS: I absolutely agree on the necessity of abandoning the imperative to – or folly of – objectivity in documentary cinema. The choice to tell the story of a ‘newborn’ state, or a state in the making, chiefly through a collection of characters (as opposed to institutions or grand narratives), foregrounds the unsettled tension between patria/matria (the perception of a homeland) and a state. Consequently it sketches a ‘national’ chronology and portrays the ‘national’ realm. The film presents a lackluster panorama (or diaporama) and unravels a stalled temporality in sharp contrast with Max’s enthusiastic aspiration for ‘nation building’, and the traces of the war/trauma and the voices of expelled Georgians appear in the voice of those who expelled them. Why did you choose to not give them a voice? What of their sense of loss, pain and uprooting? I cannot help but think of the term ‘present-absentee’, invented by the Israeli state in reference to Palestinians, while watching Letters to Max.

ÉB: You raise several important questions. But equating the Georgian/Abkhaz situation with the Palestinian/Israeli conflict produces a limited and somewhat flawed analogy. Among several noteworthy differences, the postcolonial origins of the two conflicts don’t match. Decades of Stalinism resulted in a significant Georgian population forcibly settled in Abkhazia, and a lot of Abkhaz were deported to Siberia. The Abkhaz language and culture were suppressed, and the Soviet period’s ruthless divide-and-rule policies left a ticking time bomb that exploded in 1992. The atrocity of war did the rest: scars and divisions that would not have existed in the same permanent way had there not been a war.

That said, the question you raise about one vs. two ‘voices’ in the film is really about what constitutes a ‘voice’ in the fabrication of a film. This question in turn opens up several cans of worms. Some are ideological: how should the film account for the fact that the Georgian point of view currently prevails in the Western media narrative and benefits from strong backing from the United States? Other questions are epistemological: should we think of a ‘Georgian voice’ only as the spoken narrative of a Georgian passport holder? Can voice be image? Can voice be representation? Can a six-minute montage of vacant, destroyed Georgian houses replace, or perhaps signify, an hors-champs oral narrative from refugees? Is this hors-champ oral narrative sufficient to problematise Max’s assertions that Georgian refugees should not be allowed to return?

You ask why I chose not to give voiceover time to the Georgian sense of loss, pain and uprooting. Perhaps one answer is that I felt it would be more interesting, more efficient, to let the implicit violence of Max’s ‘they cannot return, and perhaps it’s unfair, but that’s the way it is’ stand alone. No counter-Georgian narrative of suffering could substitute for the brutality of Max’s assertion. And this brutality is at the heart of the difficulties in resolving the conflict. Letters to Max is a proposition – perhaps a provocative one – that the ‘Abkhaz suffering vs. Georgian refugee suffering’ equation is inoperative, politically and cinematically, and I trust in the viewers’ ability to parse through this choice. It shifts the subject to the problems you raise, this conversation we are having, about the conflict and its cinematic forms of representation.

RS: At the heart of the film’s ‘dramaturgy’ (a more gentle word than conceit) is a question about the relevance of statehood – not about the legitimate right of an ethnocultural community to self-determination but rather about the viability of a state of the size of Abkhazia today, in the context of the European Union model on one scale and globalisation on a larger scale. These two issues are often confused and conflated. You manage to disentangle them dexterously, very clearly; at the same time, you avoid enouncing these political-theory arguments, keeping them in the realms of allegory and interpretation. As your camera observes, meditates and lingers in/on the landscape (mother/fatherland), the various ‘sites of memory’, the viewer is led to wonder how this young republic will shape its destiny and secure well-being for its citizens. What are your thoughts on the question of state formation today, the inalienable principle of self-determination and survival in a globalised, neoliberal world where the deployment of hegemony seems to be peaking?

ÉB: I think we are in a phase where the exception is becoming normalised, largely because of this confluence of factors that you have described. Living in between states used to be exceptional. Besides Taiwan, there were very few grey areas in the perfect tapestry of statehood. Look at the world today: within Europe, state borders have become abstract but increasingly rigid from without, expanding to the high seas off the coast of Libya and Tunisia to keep migrants at bay. Regionalism has become nationalistic from Scotland to Catalonia. The state has collapsed in Iraq and in Syria, at least in its Sykes-Picot form, and there are reasons to question whether multiethnic, pluri-religious states will ever be rebuilt on the ruins of two disastrous and unending wars. Kurdistan is moving towards de facto statehood, while the Islamic State has imposed itself as a de facto proto-state. UNESCO and Sweden have recognised the state of Palestine, but the symbolic significance of recognition does not yet trump the reality of Israeli colonialism. Kosovo, Abkhazia, Karabakh, Transnistria: there is a growing constellation of ‘states’ that exists outside of the United Nations. So, indeed, the state of the state is evolving towards disorder. Exceptions will become so commonplace that they will begin to undermine the axiomatic character of the system of states. And at the same time, as you point out, globalisation also renders aspects of the logic of ‘statehood’ irrelevant. The one percent live in their own transnational, abstract geography; their money moves beyond the constraints of borders; corporations exist within shelter structures that don’t pay taxes to a state. Business entities are extraterritorial. So will the state wither away, as Marx proclaimed, but for very different reasons? It will certainly not continue to exist in the nineteenth-century understanding of the concept. Perhaps Abkhazia is a kind of laboratory for its future.

A certain freedom comes with a status of exception. When we organised the Abkhaz Anembassy (2014) in Paris, somebody arrived with a box full of papers, original archives from Michel Foucault’s work on the Panopticon. He wanted them to escape and entrusted them to Max to avoid the complete centralisation and control of Foucault’s papers by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. By donating this little box to the Abkhaz national archive, he was finding a poetic way out, and some of Foucault’s papers slipped away from a monopoly by the French state •

- Event Horizon, Éric Baudelaire in conversation with Anthony Downey, Ibraaz, 2015

- Ruben Coll, Letters to Max, an interview with Éric Baudelaire, Museo Reina Sofía Radio, 2015

- Ellen Mara De Wachter, Changed States, Frieze #164, 2014 ︎︎︎

- Agnieszka Gratza, You've Got Mail, Artforum, March 2014

- Letters to Max, Poulet-Malassis Press, 2014