Heliogravures on rag paper

Various sizes

Part of the Anabases cycle

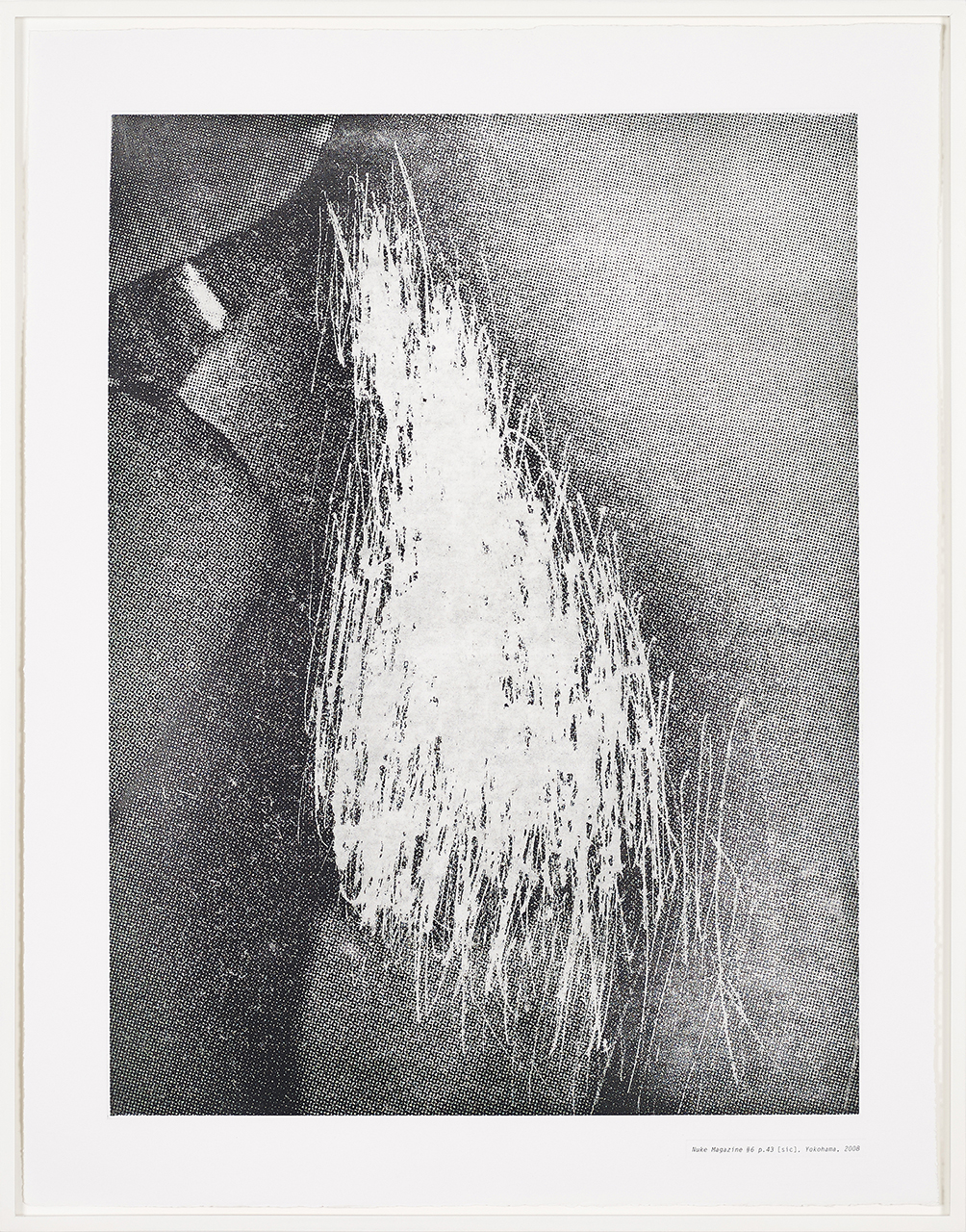

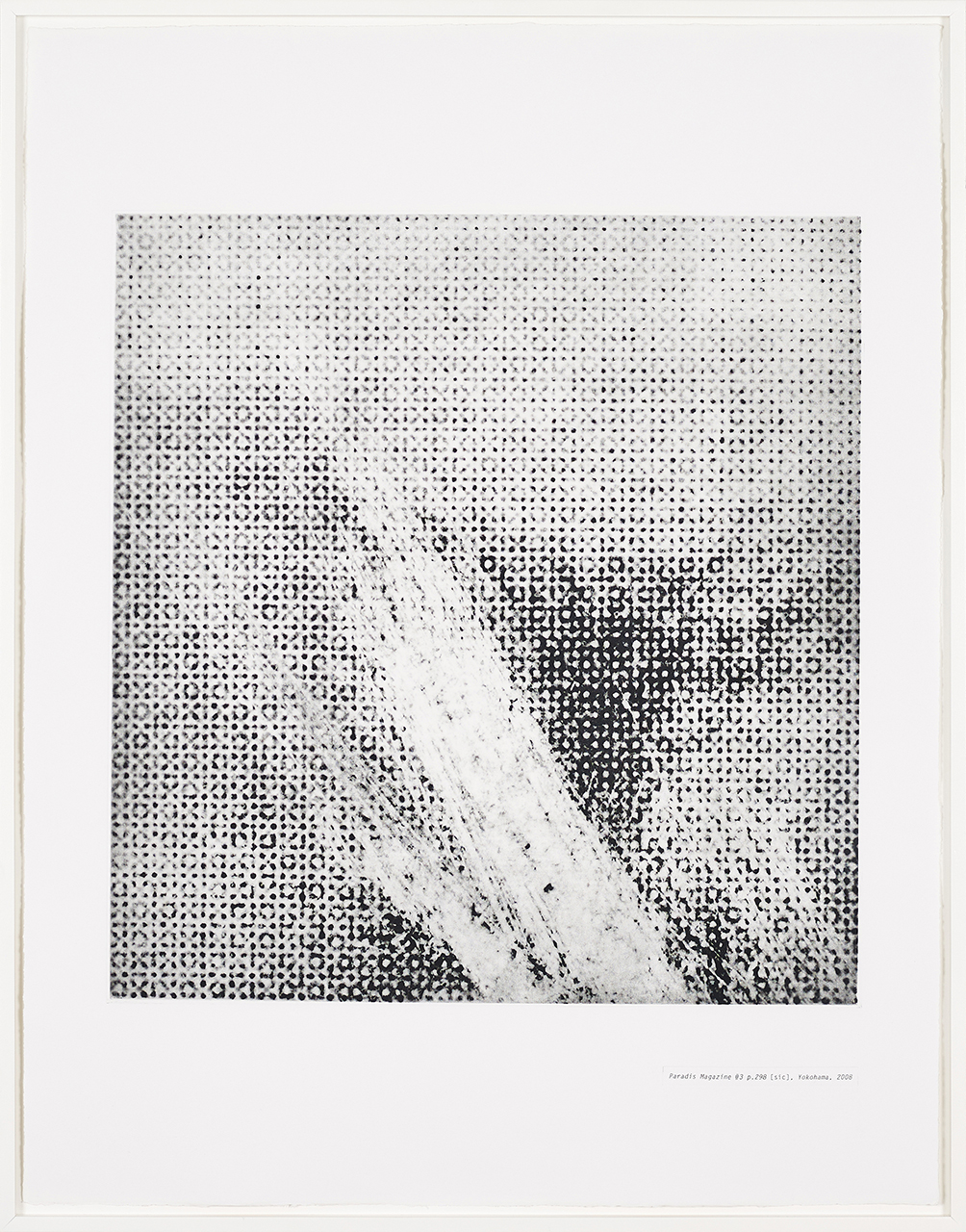

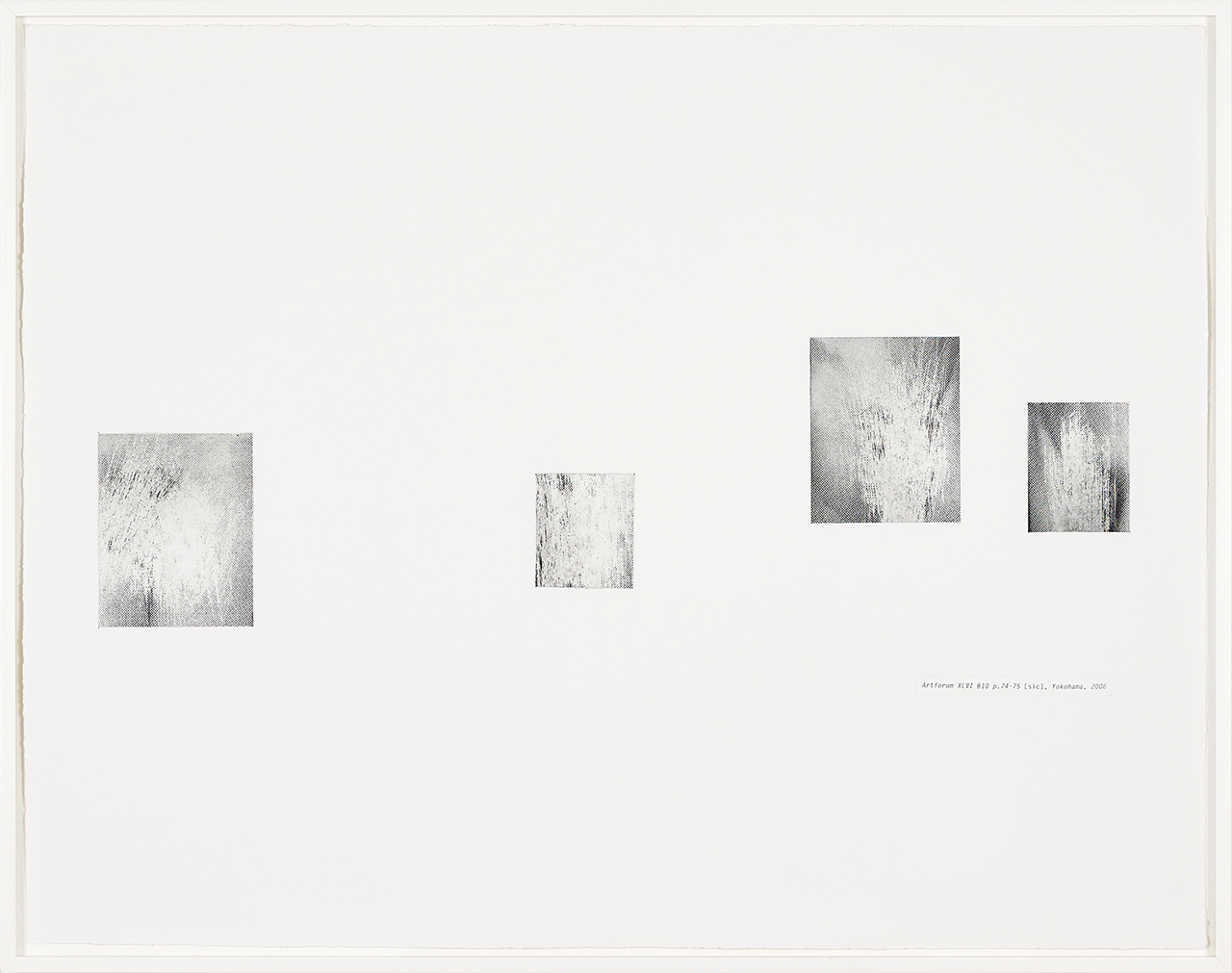

The figures on the prints are abstracted forms of scratchings, details from pages of Western art magazines bought as is in Japan. The blown-up offset printing pattern reveals the scale of the original material, and the titles refer to the source, the place and the time of their scratching by anonymous hands (e.g.: Artforum XLVI #7 p.241 [sic], Yokohama, 2008).

The process leading to the gravures retraces the itinerary and mutations of a form. In the beginning, there is an image, the reproduction of a work of art in a magazine. When the magazine is imported in Japan, foreign press distributors manually scratch out, page-by-page, all visible genitalia. The bokashi is the space where ink was removed from the surface of the page. The gravures sample bokashi from magazines bought in Tokyo and Kyoto in 2008.

The gravures also point to a paradox: what remains on the scratched page isn’t necessarily less evocative of desire, the erotic charge of an image may even be emphasized by the partial absence of the human figure. The gestures of anonymous scratchers sampled in the gravures don’t erase, they just transform the relationship between images and senses. And the gravures in turn don’t simply reproduce the forms, they pursue their transformation (through framing, enlarging and the use of a traditional western method of heliographic print making), prolonging their journey from art to pornography back to art. A round trip journey as a literal Anabasis. And a deliberately absurd typological attempt that underscores art’s ability to transcend the opposition between visible and invisible •

[sic] 2009

SD video with a chronological note

15 minutes

Part of the Anabases cycle

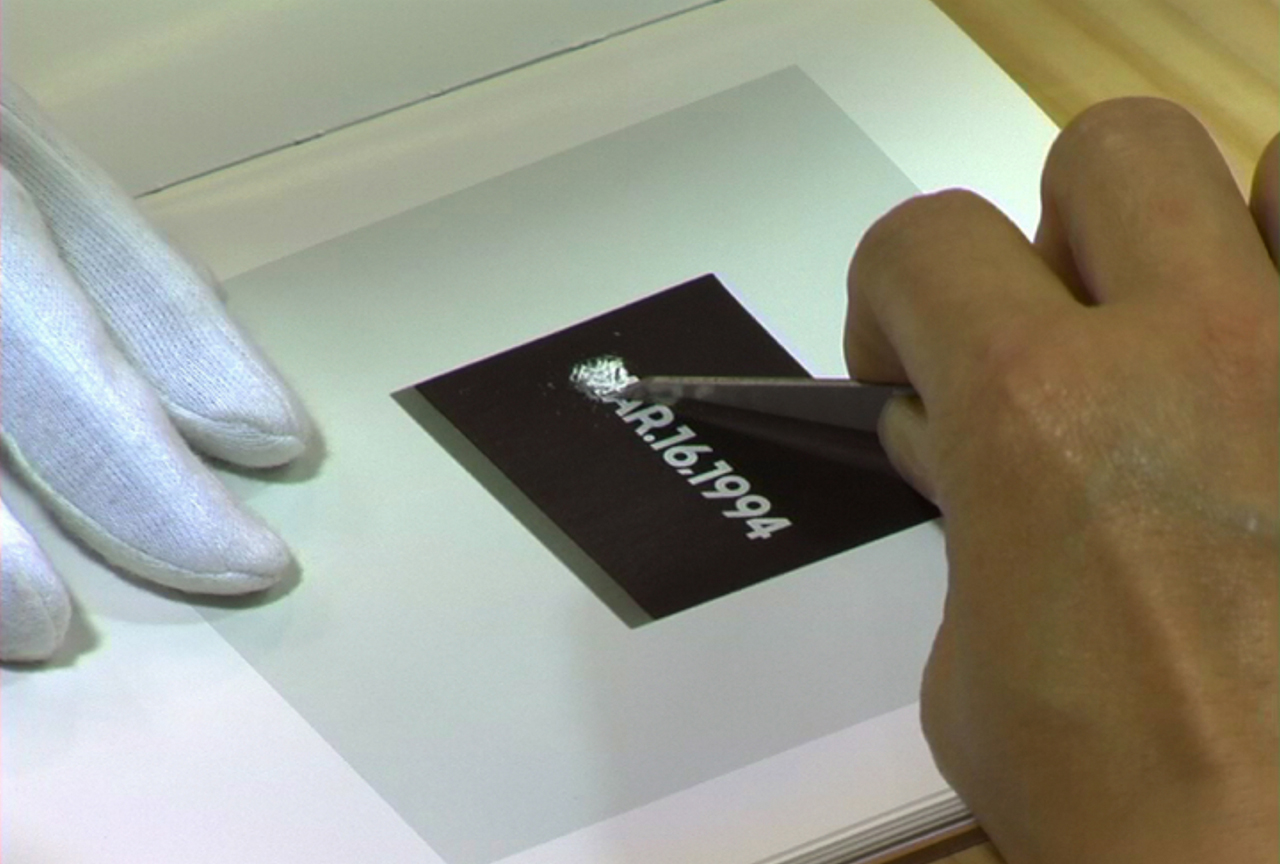

In a Kyoto bookstore, an employee receives a parcel of new books. She methodically leafs through them, scratching the surface of certain pages with a blade in an extrapolation of the use of bokashi, a Japanese practice of self-censorship wherein obscenity is defined as “that which unnecessarily excites or stimulates sexual desire.” In a poetic of the absurd, the film extends the bokashi gesture beyond the question of desire, in a ritual that doubles as a meditation on what an image does, or can do •

Chronological Note

1907 — Article 175 of the Japanese Penal Code outlaws the sale and public display of “an obscene document, drawing or other object.”

1947 — Article 21, paragraph 2, of the postwar Japanese Constitution reads “no censorship shall be maintained.”

1957 — The Japanese Supreme Court upholds a ban on D.H. Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In the main piece of jurisprudence seeking to clarify the apparent contradiction between Article 21 of the Constitution and Article 175 of the Penal Code, the high court upholds the ban on obscenity, which it defines as “that which unnecessarily excites or stimulates sexual desire.”

1976 — Nagisa Oshima’s Ai No Corrida (In the Realm of the Senses) is shown at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was shot in Kyoto, but the negative was developed and cut in Paris. As a trial balloon for a release of the film in Japan, a book containing the script and twelve film stills is published in Tokyo. In July the publisher is charged with obscenity. During the trial, Oshima requests that the high court explain the philosophical, political, legal, conceptual and practical visual standards used to define “that which unnecessarily excites or stimulates sexual desire.”

1982 — The Japanese Supreme Court declines to clarify the concept of obscenity any further, but nonetheless acquits Oshima.

2009 — In a legal and semantic grey area that remains to this day, graphic materials imported into Japan are subject to subjective self-censorship: explicit anatomical representation is replaced with ‘bokashi,’ a fogging, blurring or scratching of male and female genitalia in films and publications.

MORE RESSOURCES

- [sic] on MUBI

- Anabases, Archive Books, 2014